The ancient Greek “agon” should not be conflated with the notion of competition that predominantes in capitalist societies. Capitalist competition is a scramble for scarce resources. It is antagonistic, and competition under zero-sum constraints is always antagonistic. Under capitalism, these resources are presupposed to be scarce, treated as scarce, even when, in fact, they are abundant. As Nietzsche points out, however, the very occasion of scarcity, from the natural standpoint, is an exceptional one. Mother Nature is overgenerous. Thus, the capitalist competitor inhabits a world of perpetual crisis and insecurity—a world of perpetual exception. His frame of mind is one of desperation and the fear of an empty belly, even while he gorges himself beyond limit. The agon, on the contrary, presupposes a certain level of abundance and security, if not in actual fact, then as a matter of “principle”, or as a feeling of abundance. This “principle” is that of the polis, which embodies, really or symbolically, the already successful conquest of abundance and security as intrinsic possessions. Only now, with such a secure state of affairs as its presupposition, can the agon take place. The agon is not a struggle for scarce resources, but a struggle for mastery—of oneself and of others. In a capitalist society, one only seeks mastery for its instrumental value—the master is in a better position to monopolize “scarce” resources. In the “agonic” polity, mastery is sought for its own sake, for the metaphysical ideal it embodies: the victory over chaos, the triumph of life over the abyss. The standpoint of the capitalist competitor is precisely the opposite. He embodies the naked prima materia which, divested of all quality, seeks to swallow up everything about it in order to remedy its perennial lack.

From a socialist standpoint, cooperation is more fundamental to society than competition. And, as far as competition goes, the agon is to be preferred to antagonism. The agon is a competition to create and achieve. It is competition rendered productive, a non-zero sum conception of competition. Antagonism is an acquisitive competition, specifically the competition to acquire resources that are considered to be scarce. But, what really is cooperation? Co-operation is the operation, in tandem, of diverse elements toward a shared goal. In that sense, then, agonism, as contrasted with antagonism, is a type of cooperation. It is competition rendered co-operative, and no longer the “opposite” of cooperation. Agonistic competition, whether in the arts, in sports, or in civic activity, is a competition in the pursuit of excellence. The elements which are in competition, here, operate in conjunction toward the production of everything that makes life a precious gift. Agonism lends life the golden halo of victory.

Insofar as competition over scarce resources (or, more crucially, resources conceived as scarce) is the rule under capitalism, capitalism ushers in a universal antagonism, an antagonism so pervasive that we forget that such a thing as “agonism” is even possible. Every competitive thrust into the world of the arts is reduced to a marketing ploy. Excellence in sports is only a prelude to a career in television commercials. The beneficent animus of agonic competition becomes the grubbing pettiness of profit-seeking. This condition of the social space is only a reflection of the political authority that presides over it—the dictatorship of the bourgeoisie, the political sovereignty of the profit-motivated. The antagonistic class par excellence, the class of profit-seeking owners, remakes the social world in its own antagonistic image. It reproduces itself in all domains of human life.

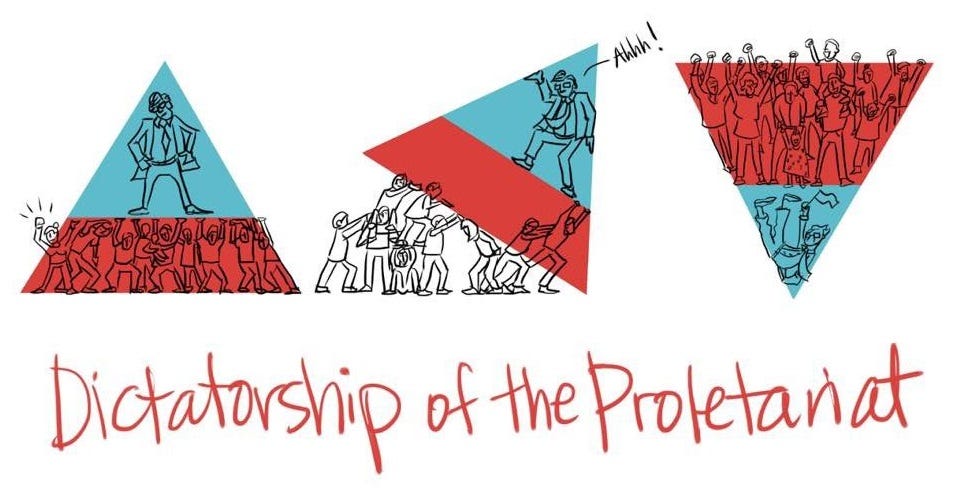

If the owner is the antagonistic class, par excellence, then the worker is the agonic one. To work is to create, and to create is to toil and struggle—to struggle against man, against nature, against oneself. Even the aristocratic artist, the ideal son of decadent leisure, insofar as he creates, acts as a worker, that is, as homo faber. Just as the bourgeoisie, through their political sovereignty, recreate the world in their own image, so will the worker, through his political sovereignty, create a world proportional to himself. The dictatorship of the proletariat is the indispensable instrument for producing and amplifying the social agon. It is itself an expression of that agon, insofar as self-discipline is fundamentally agonic. The state becomes the means through which the proletariat not only suppresses the bourgeoisie (an instance of antagonism), but through which it “suppresses” itself—that is, its means of self-discipline (which is a form of agonism), its means of self-direction, its means of coordinating its tremendous creative powers.

Democracy, which is identical with the dictatorship of the proletariat, is a top-down system in which the masses are the ones above. Framing it as bottom-up betrays a bourgeois or even pre-bourgeois subjectivity which is bound to see the masses as occupying the “bottom”. It is only from its position “up above” that the working class can exercise its creative influence on the social space. This is the “what” of democracy. The “how” of democracy is no forgone conclusion, though the connotations of “dictatorship” (which is just to say that one class dictates which conditions will prevail over society) lead many to very limited conceptions of what is, in reality, a rather generic notion.

Just as a dictatorship of the bourgeoisie can take many forms—republican and parliamentary democracies, monarchies, fascist states etc—so can the dictatorship of the workers take many forms. The dictatorship of the proletariat is a very flexible notion, and this flexibility is something which is not sufficiently appreciated. It is entirely a question of class sovereignty, of which class, worker or owner, has sovereignty over society. What they choose to do with that sovereignty, how they choose to express it, by what mechanisms they choose to enforce it—these are separate matters left to the imagination of the workers.

Additionally, it’s important to see the limitedness of our options. We really have only two options: dictatorship of the proletariat or dictatorship of the bourgeoisie. Under the industrial mode of production, all political structures reduce to one of these basic forms. There are only two classes that could hold real political sovereignty under the current mode of production, and those classes are the proletariat and the bourgeoisie. We must commit to one or the other camp. The rest is details. A false sense of options can prevent us from making a choice here. Maybe we want a “traditional monarchy”, or a “republic of the virtuous”. These are mere deferrals of the fundamental choice. How is production managed under your “traditional monarchy”? Is it still in the hands of private owners? Then your “traditional monarchy” is only another instance of the dictatorship of the bourgeoisie, and your monarch the captive of powers beyond his political reach. Have the means of production been seized by the monarch? Then he, himself, has become bourgeois, a universal monopolist. Have the means of production been seized by the workers, and subjected to collective, social ownership? Then your monarch is the figurehead and functionary of the workers, who hold the true power. We must choose—one or the other, worker or bourgeoisie. Who do you trust with the reigns of society in their hands?

“Full communism”, that is, the “withering away of the state” and a classless society, is not something subject to man’s intentional efforts, but a speculative datum of Marxist theory. It is a provisional scientific prediction, nothing more. It cannot, or should not, or need not, be enshrined as a goal. The goal of a socialist association is to establish a dictatorship of the proletariat, develop productive forces, and improve the overall lot of humanity. Again, “full communism” is a speculative datum. It is something more than an idle daydream, but less than a certainty. The “withering away of the state”, which is specifically the withering away of the dictatorship of the proletariat (not the withering away of the bourgeois state, which must be overthrown, in most cases forcibly), is, by its very language (i.e. “withering”) a passive phenomenon. A withering-away is not something done according to volitional effort, but something experienced passively. Thus, the “withering away of the state” is a prediction, not a recommendation.

Is “full communism” even something ultimately desirable or attainable? “Full communism”, were it attainable, would be a form of death, the total loss of social vitality, and an “end of history”—the most facile “universal peace” and “brotherhood of man”. No more agonism or antagonism. The “classical polis” of antiquity was a state that served as the condition of intra-class agonism, for the aristocracy, and the means of inter-polis antagonism. Likewise, with the medieval feudal order. What happened under capitalism? The agon was, to an extent, freed. Previously, it was the exclusive privilege of the aristocracy, of whatever small class constituted the genuine citizenry of the polity. Capitalism, or specifically liberal capitalism, made the social agon, in principle, open to all, though, in practice, it is rarely available to the working masses. This is a reversal of the previous condition in which it was in principle excluded from everyone but the aristocracy, but in practice attainable to anyone. Even slaves rose to prominence (the type of an Epictetus, a Luqman, or an Aesop) occasionally under the old orders, as exceptions to the rule. Under capitalism, the rule itself (“liberty, equality, fraternity”) is exceptional, and the exception, that is, the minority, the bourgeoisie, enforce all the rules. In being “freed”, the agon has become its opposite, has become antagonism, because that class which freed it, the bourgeoisie, were not equal to the task of embodying it. Agonism has been granted to us as a “right”, the “right to the pursuit of happiness” (and the most real happiness of all is victory), but universal scarcity has been interposed between everything as a limit and has reduced us to the condition of scavengers. Each class constructs the world in its own image, and a bourgeois image has nothing agonic in its contours.

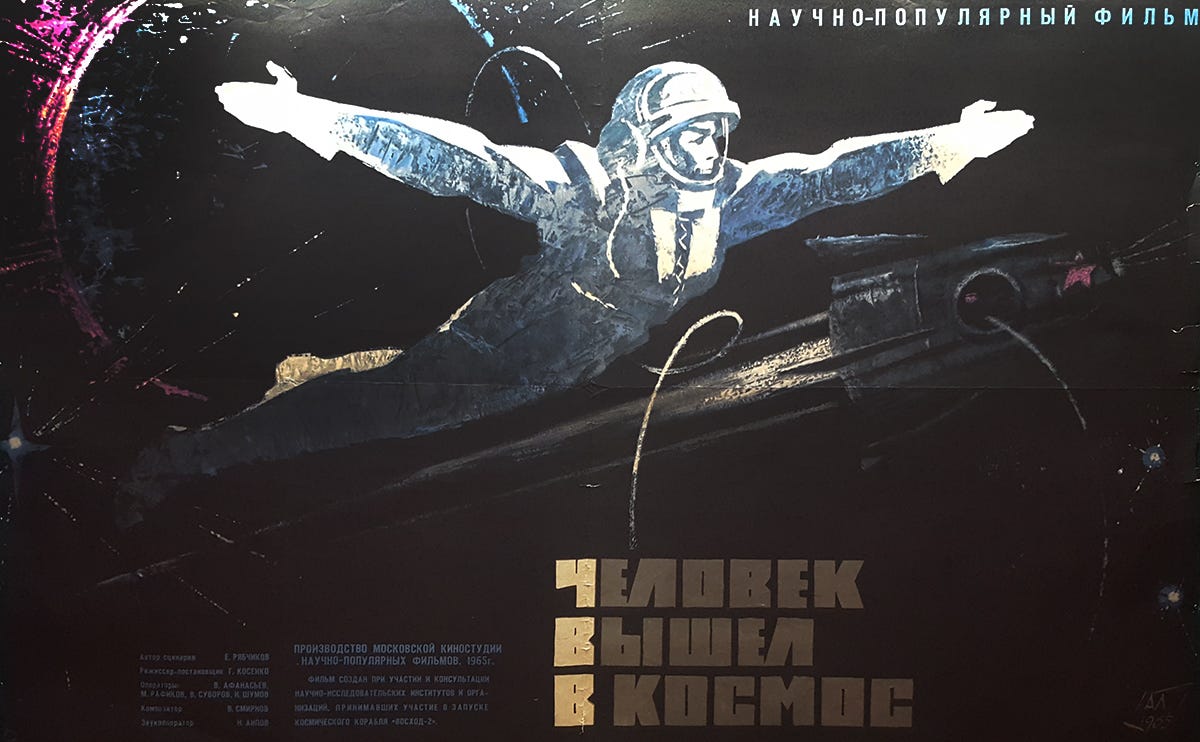

Would there really be no agonism under “full communism”? Given the speculative character of such a state of affairs, that would be very difficult to answer. It would, at the least, be a state of affairs no longer conducive to agonism. As already stated, the social space is made in the image of the ruling class, or, in the image of the political machine, in general. If the political machinery is agonistic, the whole of society, in its turn, is bound to become agonistic. Interpersonal competition would still be conceivable under “full communism”, but would it not lack real ambition, real tensions? Would it not lack a certain monumental striving? “Full communism” would be a species of comedy. The social space as a whole must be the site of tremendous, albeit fundamentally beneficent and productive, conflict. Ambition, hubris, is man's defining quality, and, the only thing that can carry him to the stars and beyond. Hubris must become his virtue.

The dictatorship of the proletariat does not mark an “end of history”, as might “full communism”—on the contrary, the dictatorship of the proletariat is the beginning of a new and limitless history, the unleashing of imagination in the service of narrating the greatest story ever told. One might almost say the the dictatorship of the proletariat is the beginning of human history, as such, that all prior “history” was a sham and mere preparation for this moment. History can only truly become human history, in earnest, when the human being (homo faber) has sovereignty, and human sovereignty only really begins with the dictatorship of the proletariat—the worker is man, par excellence, and a world presided over by the working class is a truly human world. Human history began on November 7, 1917 (the Paris Commune was a dress rehearsal).

Aristotle is, perhaps, correct in his assertion that every society requires slavery in order to subsist. Under the dictatorship of the proletariat, it is the bourgeoisie who are slaves. Their pursuit of the profit motive is instrumentalized, within a limited market sector, only insofar as it benefits society as whole, that is, insofar as it benefits the working masses who are representative of society as a whole, as well as the masters of that society. The workers constitute the genuine citizenry, and it is toward their benefit that the “bourgeois-slave” must ultimately labor. That the living conditions of the bourgeoisie are sumptuous is no objection. The bourgeoisie, under a dictatorship of the proletariat, is a species of “house slave”, a privileged slave for whom an opulent way of life serves as a concession for a second-class status. The fundamental condition of the bourgeoisie, under the worker's state, is that of laboring for another's sake; in other words, a slave. Only the worker can say, “L'etat c'est moi”.

The dictatorship of the proletariat is a permanent Saturnalia in which the proletariat is king and the bourgeoisie a slave (during the festival of the Saturnalia, in Rome, the slaves would sit at the head of the table, like lords, and their masters would serve them). That is, it is the restoration of the world to Saturn’s “golden age”, the turning of the world right-side-up. According to the Romans, it was Saturn that ruled over mankind in our golden age, and, according to Plato, even time itself was reversed under the rule of this god—everything was either upside-down, or right-side-up, depending on the perspective you adopt (to the propertied classes, undoubtedly, this seems upside-down). This golden age can be maintained indefinitely as long as the bourgeoisie are not abolished as a class. They must be maintained as “slaves”, as instruments in the hands of the proletariat (again, within a limited market sector, and the limits of that sector will be defined according to whatever the working class finds most advantageous). The polarity between these classes becomes the vitality of the polity. It should be stressed that, in this case, the dictatorship of the proletariat is not a “golden age” in the sense of utopian perfection, but in the sense of the turning of the world right-side-up, of the restoration of sovereignty to homo faber. The golden age of Saturn is not harmonious, but raucous—a festival, a carnival. The dictatorship of the proletariat takes the “hiero” out of hierarchy. It is no longer a hierarchy of military prowess (that of the aristocracy as a military caste), though, as a matter of course, the working masses must come to arm themselves, nor is it a hierarchy of the abstract, of capital and deeds of ownership, but a hierarchy of creative power—a “poetarchy” (from “poiesis”), if you will. This isn't to propose some facile meritocracy where the most creative people come to rule, but that the plasticity of the social organization itself (and it must be made highly plastic in order to serve the ever changing needs of the working class) submits itself to the creative goals of society.

The dictatorship of the proletariat in the USSR was an instrument of class warfare against the bourgeoisie, and it’s objective was the destruction of the bourgeoisie. The dictatorship of the proletariat in the People's Republic of China is an instrument for domination over the bourgeoisie, and its objective is to utilize the bourgeoisie as instruments of economic productivity. Both, I believe, are perfectly valid interpretations of the dictatorship of the proletariat, but the latter is closer to what I am envisioning here. Again, the dictatorship of the proletariat is a flexible notion. It is entirely a question of which class exercises social and political sovereignty. What they choose to do with that sovereignty is up to them. Who is going to have the audacity to tell workers what they are “supposed to do” with their sovereignty? Though some socialist have positioned themselves categorically against it, worker sovereignty must extend to allowing a market sector and the continued existence of a bourgeoisie (if they so choose). For the dictatorship of the proletariat, everything is permitted. To say that a market sector is “not allowed” under socialism is to restrict the sovereignty of the workers. The market sector under a dictatorship of the proletariat is an instance of “controlled chaos”, a chaos which is circumscribed by centralized planning and instrumentalized to the benefit of all, harnessed like a nuclear energy source. Whether the working class chooses to mine this resource or let it lie fallow is mostly a logistical question, a question of how that class wishes to administrate its rule, a question that they will have to contend with on their own terms.

I believe that the state cannot disappear under socialism. It will still be necessary, though no longer only as the enforcer of the interest of the dominant class (this, it will also be, i.e. the enforcer of the interests of the working class as against the limited national bourgeoisie), but as the guide of production. Production cannot be “free” (which is almost to say haphazard and chaotic), but, like any aesthetic production, requires form and method. Some political body, which we can call the “state”, will have to play this formative role. These are not Plato’s philosopher-kings, but rather artist-politicians. This notion of form is also teloic, not only in some structural sense of form. Goals which direct production must always be set. Man must look to the distance; to the lofty and the monumental. The stateless man is eternally nearsighted. The state, as formative power, plays the role of Prometheus for us. It is the analogue of human forethought on the social scale. It is not the forethought of a man, but of mankind. This “Promethean state” is not only an instrument of the domination of one class over another, but an instrument of society’s own capacity for self-transformation and projection of its plans into the future.

The state, primarily, as an expression of inter-class antagonism (this will be retained as a secondary feature), in other words, must be replaced by the state as an expression of intra-class agonism—the worker’s means of struggling to continually define himself and act upon the world. I am not a “statist” for the simple reason that I do not make obeisance to the state but demand that it should make obeisance to me. The state is an instrument of collective human action.