*

Idealism as a disposition: some people are never satisfied with “mere reality”. It is these “idealists” who impel humanity on to things they never before imagined—things which these idealists did imagine, things they formed through their imaginal power—beyond the all-too-real horizon. The realist wants to nail humanity to the cross of his “reality”.

*

Nietzsche as idealist of the real: even “realism” is, for some, an ideal—nothing is realistic enough for them. That is, their standards of what constitutes the “realistic” are idealistically high, beyond the limits of what their culture is habituated to conceiving. In his perspectivism, in his insistence on the tangible senses as man’s most indispensable philosophical instruments, Nietzsche demanded a greater degree of realism from philosophy than it had hitherto allowed itself. In this way, these idealists of the real introduce a higher realism into art, science, and culture—they establish a greater level of “realism” than had hitherto existed, they invent a greater level of realism than prior ages considered possible. Even realism—even reality—is invented by the idealist.

*

The idealist-of-the-real, and the realist pure and simple, are to be distinguished as follows—the realist wishes to portray some already given “reality”, and the idealist-of-the-real seeks to penetrate into its depths, to find the more-real concealed within the not-real-enough.

*

The idealist of the real as artist: the great artist (of this type) produces, in his art, something which is more real than “real life”. Their artistry produces the quintessence of life, as it were. This is as true of Homer as it is of Dostoevsky. They are alchemists of the real, not mere observers of it.

*

Could today’s realism be yesterday’s idealism? Thus, the master-slave dichotomy of antiquity was an ideal that sought to break through the straightjacket of some older realism, the realism of primitive communal existence. It dreamt of a world of greater deeds, a world that could only come to fruition through the hierarchical rule of the father, the king, the hero. The communal life of the primitive tribe was too small and too “realistic” for it. This theory would have the advantage of establishing a monism out of realism and idealism, since they are taken as one and the same thing at different times—or, rather, a dualistic monism, that is, the struggle of a thing against itself (one is almost tempted to say “duel-istic”), rather than the irreconcilable dualism of utterly separate principles.

*

The realist seeks success according to the framework of an already established “real world”, according to the particular conception of a fixed cosmos, according to its established rules and conventions. Idealism finds in this circumstance a straightjacket, too small and petty and unsatisfying, too mortal—he wants the divine, the sublime, godhood, immortality, the essential. Even if the idealist were given every advantage of mastership within this “real world” of the realist, he would be obliged, by his own nature, to cast it off, finding it too stupid, too ridiculous, too constricting to find any satisfaction in it.

*

The ideal can sometimes have its place within an order of the real as that which causes the real to defy its own rules—Zeus has his Law, but he can be won over by the intervention of a sublime and inspired prayer, if one only grasps his knees and implores with tears. In Christian terms, mercy predominates over law—the Christian mistake consists in supposing mercy to be a final ideal, a permanent ideal, one established for all time and all places. Mercy, too, can become all-too-real, a law of pity, an instinct to defer to the lowest elements of life.

*

The idealist says to the realist: “even if I did learn to play your game, and win at it, I would have to give up in disgust. I don’t want victory at the price of that pettiness. My stomach, my sensibilities, cannot abide your all-too-narrow mastership”.

*

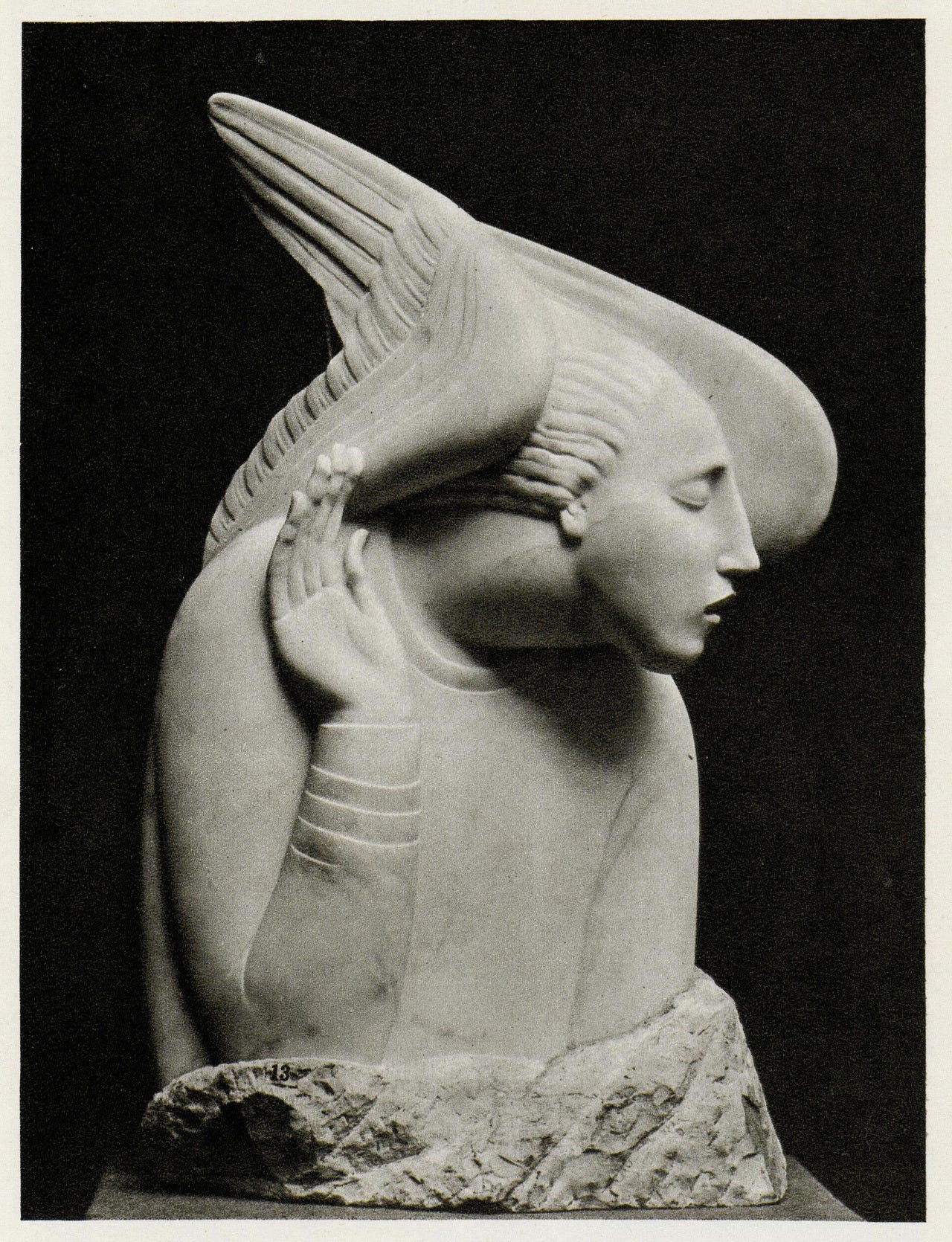

“art more real than real life”: consider the sculptures of Michelangelo—where can one find men as essentially real as those depicted in his sculptures? Flesh and blood is a cheap imitation.

*

The artist as idealist-in-deed: the production of that which is more real than “real life” is founded on a paradox. When baptized in action, the idealism of the idealist has the effect of transgressing the boundaries of the real, of making actual a vision of life beyond the narrow and already-established limits of “real life”. Idealism, of this kind, is the aspiration for the realest, for the ultimate degree of the real, of which “real life” always seems to fall short. The artist’s task, as an idealist of this type, is not only to imitate the real, but to expand its boundaries, and since the artist is the prototype of man as productive being, the production of reality can be taken as the task of “man-as-such”. The idealism of the artist is the most material of practices—not the sensory reception of a world, but the discipline of its creation.

*

The artist’s idealism is an aspirational realism.

*

It is only by modifying the real that we can penetrate into the abyssal depths of its reality.

*

The sturm und drang species of Romantic (not the historical movement, but the species) can be taken as a expression of such idealism. The delimited, harmonious, circumscribed world of the “Classicist” is experienced as too small. The Romantic is a Classicist with stooped shoulders. The Romantic is a Classicist in vitro; a Classicist in exile. He has not yet inherited his own Classicism. He is in search of a vaster world, and, insofar as he is an artist, he consciously knows or unconsciously intimates that this vaster world is never found but must be built.

*

The fraud of alchemy consists in this—why change lead into gold? They are both equally worthless. Their worth lies in the use they are put to, not in themselves. As an imperative, the injunction to turn lead into gold is a misdirection. The alchemist makes his own “gold”, even out of the discarded junk left lying in the “trash heap of history”.

*

The Romantic’s nostalgia for the past can be taken as an indicator that, sometimes, even the past eludes the limits of our “real world”. The past, in other words, is not merely the register of that which has already happened. The past is also the canvas of our future aspirations.