The Triumph of Fame; (reverse) Impresa of the Medici Family and Arms of the Medici and Tornabuoni Families by Giovanni di ser Giovanni Guidi

“Without the Long March, how could the broad masses have learned so quickly about the existence of the great truth which the Red Army embodies?” - Mao Tse-Tung, On Tactics Against Japanese Imperialism

Aristocracy and democracy have this much in common: they are both expressions of human power, a power which is concentrated in this or that class, but human power no less. Oligarchy is the reign of the abstract, of money, of exchange. The oligarch, being of a mediate essence (“exchange”), must simulate the humanity of some other class. In antiquity, it was the aristocracy that he simulated, putting on the airs of kings and lords, which were, in their most proper sense, military functions. Today, it is frequently the working masses that he simulates.

The ancient oligarch, depending on the same modes of production as the ancient aristocrat, was a kind of pseudo-aristocrat. The basic form of power which characterized the ancient world was military power, and apart from the defenses provided by either dedicated military castes (i.e. aristocrats) or armed militias (of the “demos”), agriculturally based settlements could not defend themselves from nomadic hordes who had no need of any agriculturally based mode of production in order to sustain themselves. Nor, for that matter, could settled societies defend themselves from other, competing settled societies. Today, the most basic form of power is productive rather than military. Therefore, the modern oligarch, depending on the the productive labor of the proletarian class, is a pseudo-proletarian. He invests himself with an aura of “hard work”. He “hustles” for his wealth, and therefore, naturally, he also “deserves” it. Today, the wealthy even make a point of dressing down, of appearing “down to earth”.

The oligarchy is a pseudo-class. Their class position is based purely on formality, and a pure formality is an illusion (as opposed to a formality which, at least, re-presents a concrete state of affairs). This pure formality is the fiat declaration of ownership, a declaration which, under the present mode of production, leads to the artificial scission of a private sphere of business from out of the sphere of public affairs on which the legitimation of all declarations of ownership depend. The aristocratic power was founded on an enforced monopoly over military arts and access to military equipment. Oligarchic power is founded on our belief that the oligarch has power, and our belief in the talisman of money in which that magical power is instantiated. It is, in other words, a form of hypnosis. A state of hypnosis requires that a subject relinquish their control to the hypnotist. This does not mean that such control must be somehow wrested from the subject. The most efficient way to do this is to simply convince the subject that the hypnotist already has control. The subject, then, believing that the hypnotist already has control, relinquishes their self-control on the assumption that they do not even possesses it to begin with. A hypnotist might, for instance, tell his subject to lift their arm, and then intone with an air of authority “You feel your arm beginning to grow very heavy…heavier and heavier…” and so on. Yet, it is perfectly natural that someone with their arm raised would experience heaviness. This would happen even if the hypnotist were not present. The trick lies in the subject’s becoming convinced that the hypnotist is the cause of the sensation. The moment that the subject becomes convinced that the hypnotist is the cause of such a naturally occurring reaction (e.g. as heaviness in the arms or the eyelids) is the moment that they relinquish control over to the hypnotist—because they come to believe that the hypnotist already possesses control (as evidenced by his “ability” to cause the subject’s arm to grow heavy).

That this social class seems to possess concrete power through such instruments as the police and the military is misleading. The subservience of the police and the military to the oligarchy also evidences their belief in this class’s illusory power. Under a proletarian dictatorship, for instance, police and military serve as proletarian instruments for proletarian ends, in their struggle against the bourgeois coalition. The uses of these instruments, therefore, is not indelibly fixed. They can serve the one class or the other. Theorists of the Bolshevik revolution noted that one of the crucial functions of the Soviet organizational form was its ability to integrate the military into itself. “The Soviets” says Stalin, “are the only mass organizations which unite all the oppressed and exploited, workers and peasants, soldiers and sailors, and in which the vanguard of the masses, the proletariat, can, for this reason, most easily and most completely exercise its political leadership of the mass struggle”. The subservience of these sectors to, or their union in coalition with, the proletariat would constitute an acknowledgment of the concrete rootedness of proletarian power. Their subservience to oligarchy is an expression of the reigning belief in formal illusions, and the advantages which accrue from their allegiance to these formal institutions.

One could note a further link of hypnosis to ancient (and still existing) religious practices, in the form of induced trance states, for instance, a parallel which reinforces the connection, which has existed since antiquity, of priests to monetary power. Minting coins was often the privilege of temple priesthoods, and such coins frequently bore religious insignia. Money is simply another instrument of their “magic”, an instrument of social hypnosis. The ancient Greek term for money, “numisma”, is etymologically related to that of “custom” or “law”, “nomos”—in other words, “formality”. Money always already carries with it a whole implicit legal framework, a framework necessary to guarantee trade, value ascription, and common weights and measures, that must hold good across diverse lands, cultures, and languages. Money is law. Retribution, too, is transactional—“an eye [exchanged] for an eye and a tooth [exchanged] for a tooth”.

In the ancient world, democracy was an option, among others, of governance, though one not frequently chosen. In our contemporary world, it is an entirely different matter. We do not have the same array of options which were available prior to capitalism. Our options for governance are not premised on the same bases, and much erroneous political thinking proceeds on the assumption that models of governance anciently passed down can be reproduced as “options” for us to peruse irrespective of the conditions which produced them—the assumption that one can be a “monarchist” or a “republican” in some “transhistorically isomorphic” sense. The mere image or formal invocation of an ancient model of governance is taken to be the same as its substantive presence.

“Democracy”, expressed in the simplest terms, as a political form, is when the demos (masses) have kratos (power). Voting is a secondary and incidental feature, an institutional arrangement which may sometimes affiliate itself to this political form. What, then, is the basis of democratic power, and what distinguishes between ancient and modern democracy? Furthermore, what is modern democracy?

Military power in the ancient world can be conceptualized as a kind of mediator between two competing forms of productive labor, the agricultural and the pastoral, with the pastoral constituting a more “purely militaristic” mode, the aristocratic form of life par excellence. With neither form of productive labor carrying decisive force, “on its own”, so to speak, the military power, as the common thread between them, proved the most decisive factor. The main basis of democratic governance in ancient Athens, too, was the military power of the navy, which necessitated the enlistment of large numbers of people, that is, people drawn from the demos, in order to maintain itself. Athenian military supremacy needed the “masses” (in the very qualified sense characteristic of Athenian society), and therefore the levers of power largely fell into their hands. There were many who did not count toward the determination of this mass, however, such as women and slaves. On the basis of this shameful fact, disavowal of Athenian democracy sometimes takes the form, among communists, of a total repudiation. It is as if to say that this demos-kratos has no point of contact whatsoever with the demos-kratos of the communist project (or, in some cases, the very concept of “democracy”, as such, is repudiated). This must be the case, says this line of reasoning, because this Athenian democracy is horribly stained, a democracy which is hardly democratic at all, a slave-owning and patriarchal democracy—but who is to say that the history of mass power cannot be a stained one? Who is to say that it cannot have its origin in the paradox of undemcoratic democracy? There are no such guarantees. Why should we require of communism a pure genealogy or an immaculate conception? Communism, in its capacity as a “materialism”, does not have its origin in the quasi-mythic arrangements of Spartan political life, alone, not even eminently, but just as much, if not more so, in the commercial avarice of modern capitalism and in the “imperial democracy” of ancient Athens, however uncomfortably this fact might sit with us. After all, the stubborn insistence on a noble and pure genealogy has something of a reactionary flavor to it, does it not? A project of the earth-born “hoi polloi” need not prove itself through a divine genealogy.

If aristocracy is equated with military power, then we might be tempted to characterize present day militaries as “displaced aristocracies”, aristocracies deprived of rule. This kind “transhistorical isomorphism” is typical of idealistic political conceptions, a superficial attempt to “copy paste” the outward form of a polity onto the substance of different historical context. It is precisely the same kind of “transhistorical isomoprhism” that, today, among certain sectors of the “patriotic left”, seeks to portray petty bourgeois suburbanites as the “American peasantry”. It fails to distinguish between outward appearance and inward essence, which, as per Karl Marx, is the function of science—“all science”, he says, “would be superfluous if the outward appearance and the essence of things coincided directly”. Nevertheless, granting the shaky premise that present day militaries are some kind of “displaced aristocracy”, might they not be able to reassert themselves as a ruling class? The ability of non-professional forces to frustrate professional ones in modern times (e.g. as in Vietnam), for one, suggests otherwise. For another, an aristocracy (i.e. a military caste), under the modern mode of production, cannot maintain itself autonomously as a class, whereas, in the ancient and medieval worlds, nomadic peoples could be taken as an instance of “pure aristocracy”, not dependent on the agriculturally based modes of production and therefore both the chief threat to settled life and its chief recourse for defense. That is, it was the military power, of which nomads are an instance, which furnished the chief defense of agricultural settlements. Tellingly, settled aristocracies were not infrequently drawn from the descendants of conquering nomads.

One decisive factor here is that military equipment, today, is produced by the proletariat, whereas, prior to the industrial revolution, it was mostly the prerogative of a class of people that author Yuri Selzkine calls “the mercurians”, such as blacksmiths, a non-autonomous “service-class” dependent on the major centers of production, whether setting up shop in cities and towns or forming alliances with nomadic tribes ( as mobile centers of production). The military profession was at least “in principle” able to maintain itself autonomously through nomadic pastoralism. With the production of military equipment falling out of the hands of the totally dependent class of “mercurians”, and into the concretely independent (though, politically subjugated in the present) class of the proletariat, the balance of power between aristocracy and the demos has fundamentally shifted (again, granting, for the sake of argument, the shaky premise that modern militaries are meaningfully “aristocratic”). That is, it has shifted in theory. To actualize that shift is the work of revolutionary struggle. The actualization of proletarian independence can only manifest on condition of the successful formation of a coalition, a proletarian coalition that must, of necessity, and at the minimum, include the agricultural producers, upon whom we are all obviously dependent for our sustenance. The centrality of such a union between agricultural and industrial labor, in the context of the proletarian coalition, has its emblem in the hammer and sickle.

A “return to aristocracy”, therefore, is not possible, at least not the sort of aristocracy that is pined after by reactionary traditionalists, except, as we will see later on (to be explored more fully in a separate essay), in the most distorted sense represented by Nazism. The material basis that makes aristocratic power possible is lacking. Aristocratic power, which, let it be recalled, is the power of a military caste, is predominantly founded on three bases:

The dynamic between nomads and settled life.

The difficulty of acquiring quality weapons, and the dependent condition of the class that produces those weapons, namely, the “mercurians”.

The inability of working masses, primarily agricultural labor, to train and arm themselves to the degree necessary to combat the “nomadic” aristocracies—that is, in the era proper to aristocratic rule, long before the divine gift of the Kalashnikov.

The first element here gives the aristocracy the advantage of not being tied down to one mode of production. Military life can be settled or unsettled, nomadic or agricultural (with the former, the military class constitutes itself as nomadic producers, and, in the latter, rules over the agricultural producers), as it sees fit. They do not need the mode of production (though they do need a mode of production), but the mode of production needs them—ironically, chiefly in order to defend itself from them. It is in the farmer’s interest to prop up the aristocracy, because only the aristocracy can protect him from the aristocracy. On the other hand, in a certain sense, the aristocracy does not need the farmer because, “in theory”, he can regress to a nomadic form of life.

The second element here means that the “mercurian” class of artisans (chiefly, blacksmiths) is captive to the dominant class. They are constrained to obey a self-sufficient class. Both the aristocracy and the peasant are self-sufficient. The aristocracy are self-sufficient as nomads, and the peasant is self-sufficient in the settled life of agricultural production. Under industrial production (though, one should really say “over”, since the mode of production forms the basis of social forms), the self-sufficient class, the worker, acquires the power of producing weapons. Weapons are not produced by a dependent artisanal and “mercurian” class, but by the generality, by social labor itself. Of course, it should not be taken for granted that this segment of productive labor (namely, that segment employed in the weapons industry) will necessarily be inclined to attach themselves to a revolutionary proletarian coalition, nor should such an assumption be extended to any other particular sector of the working class—this must be a case by case determination, based on the real political and social configurations which prevail at any given time. In reality, it is quite likely that, due to the lucrative possibilities afforded by their vocation, laborers in the American munitions industry will tend to attach themselves to a bourgeois coalition. Class rule, let it be remarked, is always a matter of coalitions, whether the coalition of priesthood and aristocracy, or the coalition of peasantry and urban proletariat. Classes do not, and cannot, rule in isolation.

It should also be noted that the self-sufficiency of the working class is fractured into two segments—town and country. In other words, the proletarian coalition only achieves self-sufficiency and autonomy as a coalition, when the urban proletariat is in coalition with agricultural labor (whether proletarianized or peasant labor). This will be a crucial aspect in any analysis of the situation. This is also a major reason why the union of town and country, the collectivization of agriculture, the mechanization of agriculture, liquidation of the kulaks, and so on, constitute policies which are definitive of communism in its historical unfolding. The triumph of the working class and their dictatorship, in the long term, hinges on this union, and whatever acts tend toward effecting it.

The third element, above, also no longer holds true. While it is true that, much like their peasant predecessors, today’s working class does not have the luxury of advanced military training, it is also true that they do not really need it, at least not initially. It is enough to have a gun. Special training helps, no doubt, but numbers and easy accessibility to weapons shifts the balance in their favor. The Kalashnikov has as much right to claim for itself centrality as a symbol of proletarian power as the hammer and sickle. The basis of “proletarian democracy”, of its triumphant coalition, has a triple basis in the hammer, the sickle, and the gun.

Very far from glorying in violence, however—a characteristically fascist tendency—the gun, primarily, has the significance of “peace” under proletarian dictatorship. Those who advocate for some kind of “national unity”, for a class collaborationism, too, though rather naively, do so under the impulse for “peace”. They want a “peaceful” society, a society which just is peaceful. But society never just is peaceful. The peace must be kept, the “king’s peace”, as it were. Who keeps the peace? The ruling class keeps the peace, and it is always their own peculiar peace, a peace kept by enforcing their rule, and putting subordinate classes “in their place”. The armed proletarian class, too, aims to “keep the king’s peace”, by putting its own subordinates in their proper place. Political power grows out of the barrel of a gun, and it makes all the difference in the world which class coalition is holding the gun. So much is this the case, that present day militaries, which owe their obedience to the bourgeois coalition, cannot simply have their allegiance “transferred”. They belong to the wrong class coalition. As Lenin puts it:

“The first commandment of every victorious revolution, as Marx and Engels repeatedly emphasized, was to smash the old army, dissolve it and replace it by a new one. A new social class, when rising to power, never could, and cannot now, attain power and consolidate it except by completely disintegrating the old army ('Disorganization!' the reactionary or just cowardly philistines howl on this score), except by passing through a most difficult and painful period without any army (the Great French Revolution also passed through such a painful period), and by gradually building up, in the midst of hard civil war, a new army, a new discipline, a new military organization of the new class”

Modern democracy, concretely, must mean public ownership of the major means of production and the supremacy of the proletarian coalition. This is an actual, concrete expression of popular power, just as, in the ancient world, the participation of the “masses” in the Athenian navy was an expression of concrete popular power, especially insofar as military power constituted political power, “as such”, at that time. Today military power is divided in a contest between mass-based non-professional forces, and professional forces. Even within a socialist state, if the bureacracy and the military feel that they can treat the masses with impunity, the power of this mass-base is reduced to nil, but if a need to defer to this mass asserts itself, as a political necessity, then the mass retains its power in proportion to the degree of deference. To the extent that this mass asserts their dominance successfully, they are able also to professionalize themselves under the auspices of a proletarian dictatorship (the Soviet organizational form, as already mentioned, is a channel for uniting these two functions). A vote is an expression of formal, not actual, power, both in the ancient case and in the modern one. Naturally, to be fully democratic, both the formal and the actual are necessary, but a formal expression of power which is not founded on an actual basis (in the one case military, and in the other productive) is no power at all, but illusion. Modern democracy, therefore, is necessarily a proletarian dictatorship, and nothing else. That which passes itself off as “democracy”, today, is really the purely formal disguise of oligarchy.

It is only in our time, under the current mode of production, that democracy becomes socialist—that is, that democracy bases itself on socialized labor. This, and only this, is, in the words of Mao, “democratic both in form and substance”. In ancient Athens, democracy was military, and the demos consisted, primarily, in those able to participate in military service—democracy was, in a manner of speaking, “socialized aristocracy”, demos in form and aristocratic in substance. The outsized importance of the navy meant that kratos, in this social setting, objectively fell on the shoulders of the military age, male demos, and the scope of this kratos could only be increased through an expansion of the Athenian maritime empire, i.e. by rendering the city-state more dependent on this military power. Put another way, the demos (the “socialized aristocracy” of Athens) secured its kratos, its power, by expanding empire, thereby rendering itself indispensable as a military caste (that is, as a kind of aristocracy), lest the empire collapse. The kratos portion of the demo-kratic equation, under industrial production, on the other hand, issues from the unrivaled supremacy and dependence of all on this mode of production. Recall that in antiquity and the middle ages, it was precisely the tension between pastoral and settled forms of life that elevated military functions to the position of social supremacy which they, in fact, possessed at that time. The encounter of Cyrus with Tomyris, the Greek fear of quasi-mythological “Amazons”, the opposition between “Iran and Turan”, the great Khans of the steppes—all so many instances of this dynamic. That ancient Athenian democracy was no less militaristic in its character than various aristocratic polities stricto sensu of that period is not an accidental feature, but the essential one—the demos of Athens were an accident of military (in their case, primarily naval) necessity. In lieu of a supreme form of productive social life, military functions raised themselves to a mediating supremacy, standing between this and that form of social life, chiefly, the nomadic and the settled. In the modern period, there is no alternative to industrial production. Those nation-states that have offshored production have via this same gesture cemented their utter dependency on the “world industrial state”. The kratos of the modern demos, then, is increased not through military conquest, but through measures taken to seize the means of production and improve their own living conditions. These measures to improve the standard of living are not primarily undertaken for “humanitarian” purposes, but are practical measures intended to secure power. Production is power, and therefore the power of production is tied with the power of the producers themselves. The improvement of this class’ condition of living is the precondition of its power, and its power is the precondition of its capacity to improve its own condition of living. This is a matter of the starkest realpolitik.

Thus, the formality of the vote, in Athenian democracy, was but a re-presentation of the concrete, military function. What was present, concretely, as maritime empire, re-presented itself in the Athenian elections, in their love of speech-making and assemblies. The “divine right of kings”, too, was, initially, premised on concrete military necessity, the organization of the aristocracy into a feudal structure, but owing to tremendous changes in production and military technology, with its concomitant social repercussions, this institution resolved itself into a more or less purely “formal monarchy”. The original divine insignia of the aristocrat's right to rule was the might of his rule, the might of his class. The force of aristocratic arms, and society's dependence on that force, was the very the sign of God’s pleasure in their earthly dominion. As society came less and less to depend on this class to provide for its defenses, that right retreated behind a veil of pure formality—no longer an authentic re-presentation of military presentation, but a mis-re-presentation, the re-presentation of what was no longer present. All monarchs, hence, became sham monarchs. Their right to rule no longer stemmed from the God-given charismata of valor and strength, but from a God-given fiat—the aristocrat rules “because God says so”. He, thus, increasingly came to resemble the priesthood, whose authority likewise stemmed from divine fiat. The French Revolution rejected king and priest as one and the same holy lie. What this revolution replaced the holy lies of king and priest with was another formality, that of “liberté, égalité, fraternité”, a formality which can only find its concrete presentation, in reference to which it stands as the re-presentation, in the social and political rule of the proletariat. This formality is destined for a certain class. Until then it must remain a mere formality, an illusion, that is, a mis-re-presentation.

Indeed, the very stability of bourgeois rule is in proportion to this class' ability to fool, to produce illusions. Summarizing the views of another conservative thinker (F.J. Stahl), the political theorist Carl Schmitt writes:

The hatred of monarchy and aristocracy drove the liberal bourgeois leftward; the fear of being dispossessed of his property, which was threatened by radical democracy and socialism, drove him in turn toward the right, to a powerful monarchy whose military could protect him. He thus oscillated between his two enemies and wanted to fool both.”

If illusions, therefore, are to reign, then who can compete with the oligarch? Neither the decadent aristocrat divorced from his former strength, nor the priest divorced from his former monetary jurisdiction, can compete here. Their illusions are sterile. The illusions of the oligarch are fertile. The power of the oligarchy is an illusion which is productive of other illusions. The oligarch is a proletarian of mirages working at the mechanism of a dream factory. His power rests on the illusion of a fiat declaration of ownership, and in order to maintain that power he must constantly produce new illusions: the illusion of the voting process, the profusion of illusory words and concepts—a “democracy” which is not democratic, “liberty” which is a servitude to his class, “philanthropy” which is the distribution of crumbs from a stolen pie. In the land of dreams the dreamer is king, and the oligarch is the dreamer. It is his dream in which we all live. It is a dream from which even he could not rouse himself if he wanted to (and why would he, since it is so pleasant for him?). The task of awakening belongs to one class alone, the revolutionary class, the class of “democracy” in the strict sense of the term: the proletarian coalition—because ownership is merely a formalized, abstract image of command, of concrete presence and activity at the site of production. The bourgeoisie own the means of production—the workers will come to command them, in the most direct sense. Bourgeois ownership is a re-presentation in the market of proletarian presentation at the site of production, and in that sense is necessarily a mis-re-presentation. In declaring himself owner, the bourgeois re-presents himself as producer. But bourgeois ownership is merely passive, and if the re-presentation is passive then the presentation, seen through this distorted lens, will also appear like a passive, a merely “natural” phenomenon. This mis-re-presentation, however, has been an efficient mechanism in the continual expansion of productive forces, an illusion whose pursuit (in the form of profit-seeking) has resulted in the expansion of productive forces and increased the socialization of world labor. This mis-re-presentation has solidified the very presentation that will overthrow it. Bourgeois society is, in that sense, not just an ordinary dream, but a prophetic one, and the dream-image of ownership symbolically presages, through a glass darkly, the full-flowering of command over the forces of social production.

At the present time, therefore, “democracy” has both a formal and a concrete meaning. The superstitious (because it believes in ghostly forms without substance) belief that casting votes in a bourgeois election is in any sense “democratic”, that is, the belief that formal re-presentation through voting can be meaningful apart from the concrete presentation of proletarian power, can be termed “democratism” in order to distinguish it from democracy in the strict sense of the political sovereignty of the masses. Democratism is not democracy. Democracy is power, and democratism the illusion of power, a formal re-presentation with no corresponding presentation. Communism, therefore, must discover a democracy apart from “voting”, through proletarian dictatorship. “Voting” does not constitute the essence of democracy. When we mistake it for its essence, we elevate mere procedure over concrete power, and democracy is thus reduced to mere formality, reduced to democratism. Voting as a procedural factor in “real democracy”, that is, as an instance of the delegation of authority and enforcement of will in proletarian dictatorship, has its place, but “voting” cannot constitute an actually democratic practice without the corresponding seizure of power by a proletarian coalition. That is, voting can only be meaningfully demo-cratic if the demos are in power, if this procedure is implemented by the demos, as the re-presentation of its concrete power—the “demos”, in this context, can only be the proletarian coalition, and its “power”, its kratos, is productive power. “Voting”, in other words, is only a procedure—we must ask: who is employing this procedure, and toward what end? Procedure does not exist in a political vacuum. Democracy, substantively, is the kratos (power) of the demos (masses). Too much emphasis on “voting” trivializes that power. Insofar as the people have power, and that power is congruent with the social forms of industrial production (since industrial production is the primary social form of the demos in the present era)—that is “democracy”, regardless of the manner in which this power is institutionally and procedurally manifested. It is power, first and foremost, not “well-being” or “prosperity” which characterizes proletarian dictatorship. That the masses are “taken care of”, as if it were an act of charity, is not sufficient. We must ask: who is it that “takes care” of them? Since power is primarily in question, it must be themselves alone, through their functionaries and institutions, all of which owe their allegiance to a proletarian ruling class. There are no pre-given rules as to the institutional forms which proletarian dictatorship is obliged to take. As Lenin puts it, “The transition from capitalism to communism is certainly bound to yield a tremendous abundance and variety of political forms, but the essence will inevitably be the same: the dictatorship of the proletariat”. The concrete presentation of proletarian power may re-present itself in any way that “makes sense” of the historical, social, and national conditions of a given situation. This re-presentative activity even extends to the re-formation of other classes along lines amenable to that of the ruling class. Just as the bourgeois class seeks to domesticate, as far as possible, the proletariat , mobilizing toward this end not only the repressive arm of law enforcement, but also the stultifying forms of public education, so too the proletarian class, as masters of society, will re-form other social classes into whatever shape proves serviceable to proletarian interests. Says Stalin:

“The dictatorship of the proletariat, the transition from capitalism to communism, must not be regarded as a fleeting period of 'super-revolutionary' acts and decrees, but as an entire historical era, replete with civil wars and external conflicts, with persistent organisational work and economic construction, with advances and retreats, victories and defeats. This historical era is needed not only to create the economic and cultural prerequisites for the complete victory of socialism, but also to enable the proletariat, firstly, to educate itself and become steeled as a force capable of governing the country, and, secondly, to re-educate and remould the petty-bourgeois strata along such lines as will assure the organisation of socialist production”

What is “anti-working-class”? It is all that which opposes their dictatorship, their supremacy over the Earth, over the real seat of their power. To merely desire a world in which the workers are “taken care of”, and to construct this as the possible horizon of politics, is to be “anti-proletarian”. Even the gains which the working class wrests from the bourgeoisie, under the latter's rule, should be understood as the assertion of an incipient proletarian dictatorship, not as a mere concession from above. For our “patriotic socialists”, the notion of “anti-working class” is primarily anchored in the exigencies of the “culture war”. All that which falls on the “wrong side” of this culture war is deemed “anti-working-class”, and all that which falls on the “good side” of this same pseudo-conflict is deemed “authentically working class”. Thus, only those members of the working class which exhibit all the doctrinally correct positions on this all-important culture war, are deemed authentic members of that class, and hence “authentically revolutionary”—what is this, if not a highly distorted left-communism? Doctrine is an instrument for the self-clarification of proletarian struggle and rule, not a heavenly law to which the proletarian coalition owes its obedience. Nor could a proletarian coalition be stably founded upon the quicksand of such ephemeral media trends. A political coalition must have a political character, that is, a character whose basis is in the “polis”.

Man is a political animal, as Aristotle puts it, and it is not for him to determine the scope of the polis through his fleeting whims. That scope is given to him by the conditions which he himself has patiently built up throughout his history. The poleis of Aristotle’s day included the city-states of the Greeks and the imperial cosmopolis of the Persians. “Objectively”, the cosmopolis was the true polity of antiquity. The horizon of immediate social being is the fulfillment of needs, need which, moreover, are not simply those of “bare subsistence”—they are social needs. The fulfillment of social needs, at that period, required trade in various luxury goods, the maintenance of trade networks and communications between various “city-states”. Hence, the imperial aspirations of Cyrus, Alexander, the Caesars, etc, were no mere expression of personal hubris. They were rationally justifiable measures (whether or not they were “moral”) undertaken to re-present the actual contours of antique society, its real presence as cosmopolis, according to a political form—the political union of cities under a sovereign as an image of the cosmopolitan ties already existent in their trade relations, their already existent social unity re-presented as imperial hiero-arche.

In our day, the horizon of social needs circumscribes a planetary polity. Heavy industry, communications technology, the silicon chip, transportation and infrastructure—all of these factors have outlined the contour of a de facto polis, and that polis is global, or better yet or “planetary”, as Bukharin would have it, whether we like it or not. The Earthly horizon is either “planetary” or “global” depending on which class is viewing it, and whether that position is one of power of subjugation. In Bukharin's words:

“The immediate natural (earthly) environment of human beings in society will undoubtedly produce much more diverse impressions because the orbis terrarum (known world) of each person will expand to planetary horizons, to the planet as a whole.”

The communist doctrine of “internationalism” has no other meaning but that the polity of industrial society is concretely the Earth itself, and that communist political struggle should adequate itself, organizationally, to this concrete reality. “Globalism” is merely a formal re-presentation of an already existing state of affairs, but a re-presentation with the subjective stamp of a certain class coalition, that of the modern day bourgeoisie, finance, technocrats, and an assortment of other sordid alliances. “Internationalism”, too, is but the re-presentation of the already-existing planetary-polis, but with the subjective stamp of a proletarian coalition. Both coalitions seek but to master a situation imposed by objective, historical necessity—the situation of the real polity, the situation of planetary industry. Only the petty bourgeois strata, the most regressive of classes, still dreams of various “localisms” and self-enclosed nationalisms.

To be clear, man does determine the contours of the polity, but he does this historically, not whimsically, through historic struggles and developments, not through extemporaneous declarations as to what is “good” or what is “bad”. The degree to which globalism is “bad” is entirely immaterial (pun intended). The world is built up by man, but not in a moment and not by one man alone. It is the patient labor of the generations of man, and man, socially, is divided into classes. Today, only the proletarian coalition is political in the “classical” sense. They are the true polity, an international polity, a planetary polity.

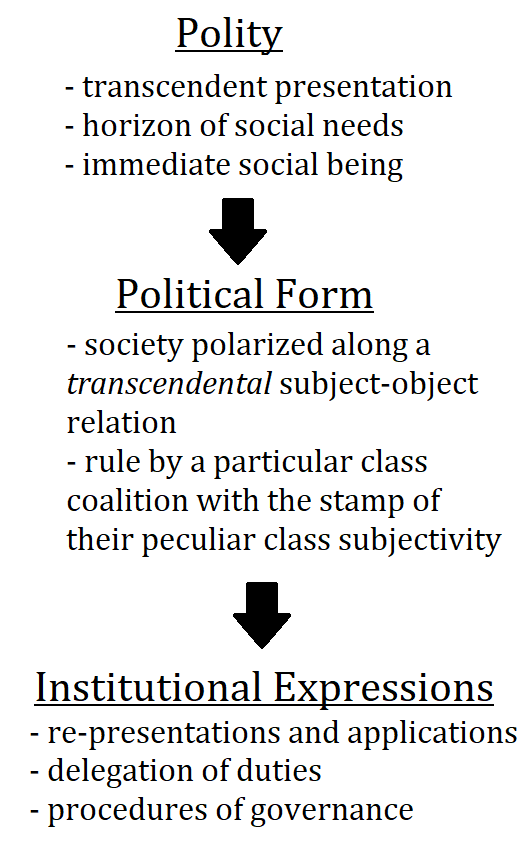

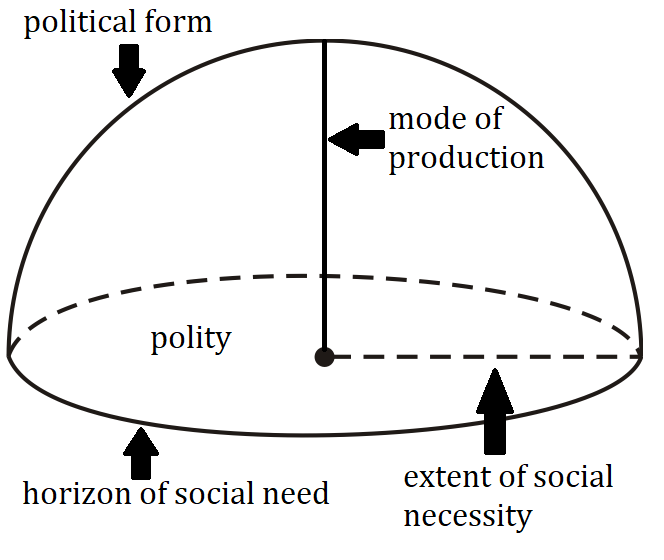

The term “polity”, here, designates the concrete presentation of society, its intelligible form. “Concrete presentation” belongs to ontology and metaphysics, though not as these terms are conventionally understood today—that is, it belongs to the immediate being of society, prior (ontologically) to the split between subject and object. The polity is anchored in the “material reality” of a nation, community, or, indeed, in the case of industrial modernity, of the Earth itself. “Polity” is, in effect, a specification of the broader concept of “material base”, and in which this base is scrutinized in its capacity as the intelligible ground out of which political forms, laws, and institutions “emerge”. Political and institutional forms are subsequent to the polity. The proletarian dictatorship is a political form, premised on the rule of a certain class within this polity—a class subject establishes its dictatorship within the space of the polity, self-consciously polarizes the polity into an object for a certain class subject. Present day “political forms” reflect the social development of industrial society (i.e. the modern polity), and they does so through the rule of a certain class or constituency from within that polity, either the rule of the bourgeois coalition or of the proletarian coalition. The immediacy of social presence is polarized along the lines of subject and object, with a certain class from within that social totality taking on the mantle of a privileged political subjectivity. The institutional forms in which this political form can represent itself may vary. This can be roughly schematized as follows:

In the modern context, that is, in the context of planetary industry, the assertion of political class-subjects generally necessitates the carving out of a space within the planetary polity, either in the form of bourgeois nation-states or in the form of “socialism in one country”. The planet is a singular industrial polity, but a polity which is politically contested, that is, subject to class struggle, both within classes and between classes. The nation-state, whether bourgeois or proletarian, in the present context, is never a polity as such, but always possesses a derivative character in relation to the planetary polity—a regional, cultural, and historical specification within the space of world industry. This is a contest over which class or class fraction will usurp the privilege of re-presenting the planetary presence in its own image. The ground of every national political form, in this era of industrial modernity, is always the planet as a whole, and never just the parochial limits of some culture or civilization. The only parochialism left to man is the parochialism of humanity and the Earth.

The dictatorship of the proletariat is the formal expression of a really existing polity. The relation can be represented as follows—the polity is the intelligible social whole whose central axis is the mode of production, and whose periphery marks the general limit of social needs, and “over” this whole a certain architectonic structure erects itself as the general structure of formal political rule (rule which necessarily belongs to a certain class) which is characteristic of this underlying “whole”, and particular state institutions, in turn, consist in specifications of this “generic” structure. In this diagram, the particularity of institutions find no representation precisely because the diagram is a generic representation, and hence necessarily lacks all those particularities that furnish concrete existence with its irreducible presence:

One might say that the polity is intelligible and “transcendent”, the architectonic structure of the political is rational and transcendental, representing the rule of a certain class subject (a class subject that always has the form of a coalition, whether it is the coalition of aristocracy and priesthood, in the middle ages, or the present-day bourgeois coalition) over the “object” of society, and the institutional forms which specify and particularize this architectonic structure re-present so many historical and cultural contingencies in relation to the transcendental “a priori categories” (in this context, the intrinsic “tendencies” that structure a class' subjectivity “in advance”) that condition them for the subject (the class subject). To express this in terms specific to the present historical era, one can say that there is an underlying planetary polity implied in the concrete and intelligible social whole whose central axis is the industrial mode of production. This social whole is transcendent in the sense that any rational schema that attempts to account for it can only be retrospective to the immediacy in which this social whole is actually lived, in which this social whole actually is—it transcends the subject-object dichotomy. It pertains to being, to social being, not to rational concepts, which follow in its wake and attempt to formalize its totality by means of various schemata. The general form of proletarian rule, as an expression of this polity, is proletarian dictatorship, and likewise bourgeois dictatorship in relation to bourgeois rule. This class dictatorship, in turn, can specify itself in a multitude of particular institutional forms. There is no one possible way of institutionally re-presenting class rule. Again, we cite Lenin: “The transition from capitalism to communism is certainly bound to yield a tremendous abundance and variety of political forms, but the essence will inevitably be the same: the dictatorship of the proletariat.” These forms particularize the sort of relations that ruling class subjects will have with society as its “object”, although, always underlying this subject-object relation is the originary polity in which subject and object constitute an indissoluble whole, in which the intelligible whole of the polity simply is what it is.

A dictatorship of the proletariat can be a democracy (in the purely formal sense of “democratism”), it can be a republic, it can even be “aristocratic” or monarchical. After all, why not? Saudi Arabia is no less a bourgeois dictatorship (in its political form) just because it re-presents itself as a monarchy (in its institutions). A monarch may be a functionary of the proletarian class in just the same way that they may be a functionary of the bourgeois class—whether not such an institutionally monarchical proletarian dictatorship is at all desirable is a separate question. The origins of proletarian dictatorship, in the underlying polity, are not “statist” (in the sense of state institutions), but political—i.e. in the polarization of the polity according to the privileged subjectivity of a certain class (or class coalition). Formulating the concept of the proletarian dictatorship exclusively in terms of a “state” is an error. It is something prior to state institutions, something which expresses itself in state institutions. This dictatorship is not identified with the state, but is the generic form of a state ruled by a certain class within the context of a certain polity. The modern dictatorship's power of dictation issues, first and foremost, not from the state, but from the triumphant class and the seat of its concrete power in the industrial and agricultural base, that is, it issues from the grounding of a political form in the polity. The state, as the institutional expression of this concrete power, arises as a re-presentation of the latter. This concrete seat of power is the underlying whole which is constitutive of the polity, and the proletarian dictatorship is the generic form of the proletarian institutions that reflect this polity, a generic form that specifies itself in particular institutional arrangements that are, in turn, bound to express themselves in a diversity of forms contingent on historical conditions, national peculiarities, cultural inheritances, as well as explicit theoretical considerations.

If this underlying polity is the planetary network of industrial and agricultural production, then this polity is a proletarian polity, even prior to the self-consciouss assertion of this class as a class-subject. The proletarian class is thus not only able, through organized class consciousness, to master this poilty—they are this polity, its very substance. They are grounded in the polity. The industrial polity is their way of being, their social immediacy, not that of the mediate bourgeois class. This is why the bourgeois class, as mentioned above, must re-present itself according to the ideological image of the “entrepreneur”, the hard-working businessman, the hustler. This class brings industrial goods to the marketplace as if they were its own productions. The bourgeois class is not a presence of industrial modernity, but a ghostly and abstract re-presentation of it. The proletarian class is, firstly, the living presence of industrial modernity, and, moreover, has the capacity for organizationally re-presenting itself as the political masters of modernity. Thus, the proletarian polity already exists, and has existed from the moment industrial production was ascendant—it simply lacks the state institutions through which it can impose its social will, in a “top-down” direction. In the context of proletarian dictatorship, state institutions and a bureaucratic apparatus are the efficient mechanisms through which the working class transmits its authority in a top-down manner, but not the basis which constitutes their power. That is, it is the proletarian state that does not yet have existence, not the proletarian polity (excepting, of course, the already existing revolutionary proletarian states of “Actually Existing Socialism”). From this it also follows that bourgeois dictatorship does not and never has had a corresponding “bourgeois polity”. It has always and ever been nothing other than a formal imposition over, a mis-re-presentation of, an already-existing proletarian polity. This formal imposition originates from within the proletarian polity, from a hostile class that has, from the very beginning of this polity, “hijacked” it. Yet, at the same time, this hostile class has also, in spite of itself, birthed this new polity, through the process of primitive accumulation and re-investment which led to the development of socialized industrial production itself. The bourgeois class are not only a sort of hostile and “alien” force within the present proletarian polity, but were also such an “alien class” within the preceding aristocratic-agricultural polity. In supplanting the latter they have brought about the former, but never have they brought about, and never could they bring about, a polity unique to and characteristic of their own class. This is because they are an intrinsically mediate class who depend on “concrete priors” as already-given. The bourgeoisie were, in a manner of speaking, merely the stewards who oversaw the construction of the great edifice of the proletarian polity, “in the king's absence”, and now that the rightful kings of this polity demand authority over their inheritance, the corrupt stewards, grown comfortable with power, obstruct them from seizing what is rightfully theirs. In their greed, these stewards have, as a frequently repeated quote puts it, provided rope for the nooses on which they will be hung.

In a sense, then, bourgeois dictatorship is a political form belonging to the proletarian polity. It is a political form in which a mediate class, a class which belongs to this polity, the masters of money and exchange, have taken the reigns of power from the class “on whose behalf”, as it were, they mediate. Mediation, after all, is always between this and that. Mediation is a relation, and its structure, “in itself”, is primarily formal and rational. What it mediates is concrete, and it is, as a mere mediator, dependent on these intelligible nexuses of concretion, if it is to be able to mediate at all. In other words, a class with a mediate function must already have something which is susceptible of mediation, if it is to be able to do any mediation at all. Moreover, the proletarian class is no less rational than the bourgeois class—they do not need such a mediate class. They can mediate (“administrate”) their own affairs. The bourgeois class, on the other hand, does nothing but mediate, as their peculair activity, their “praxis”, and nothing but merely rationalize and justify an already-existing state of affairs, in terms of their theoretical reflection, their “ideology”. That is the difference between bourgeois and proletarian classes. One is limited by mediation, and the other has mediation at its disposal. One employs rationality as the instrument of production and development, and the other merely rationalizes that which already is.

Undoubtedly, for any familiar with his thought, much of what has been said thus far will suggest a number of concurrences with the writing of Carl Schmitt (who was briefly quoted earlier on in this essay). In particular, the friend-enemy distinction, the question of sovereignty, and the state of exception, will appear most relevant to these reflections on proletarian dictatorship. “Who are our enemies? Who are our friends? This is a question of the first importance for the revolution”, says Mao, and an acolyte of Carl Schmitt might be inclined to nod in agreement. So, too, Stalin tells us “the dictatorship of the proletariat is the rule—unrestricted by law and based on force—of the proletariat over the bourgeoisie”. The theoretical concurrences here are, however, more on the superficial side—or rather, it is Schmitt who errs on the side of superficiality. The communist theory of the proletarian dictatorship endows Schmitt with substance. “To distinguish real friends from real enemies”, says Mao, “we must make a general analysis of the economic status of the various classes in Chinese society and of their respective attitudes towards the revolution”. From the communist standpoint, the questions of sovereignty, of friend and enemy, and of states of exception, are little more than theoretical IOU's unless backed by the substantive guarantee of class. Class is the substance of politics. Can one square this with the Schmittian formulation of sovereignty?

Herein we will discover where the superficiality of Schmitt lies. It will be found to lie in the same “magic”, alluded to at the beginning of these reflections, which is exercised by the bourgeois class whenever it, or its theorists, erect mere formalities as substitutions for and mis-re-presentations of concretion. Just as bourgeois liberal thought divests “fraternité” of any substantive class character, by rendering it the brotherhood of “man in the abstract”, Schmitt too divests the demos of this “democratic age” of its class-based specifications. The Schmittian demos is not a class with its own class-subjectivity, its own peculiar interests and and will to be asserted in the social domain, but an undifferentiated Volk to be appeased by a mis-re-presentative sovereign institution (a mere institution). Hence, the Schmittian conception of sovereignty is not even transcendent. “Transcendence”, in the authentic sense, is not an up-there-somewhere, but the supercession of the subject-object distinction—that is, it is the supercession of the transcendental condition. It is the immanence of the polity which is authentically transcendent, and the polity of the present age is substantively a proletarian one. “Immanence” is not the opposite of “transcendence”—it is a mode of transcendence (not excluding other such modes whose elucidation does not lie within the scope of the present essay), and transcendence is the ultimate degree of concretion, beyond the insubstantial ghostliness of the transcendental subject.

In the introduction to Schmitt's “Political Theology”, we find the following rather flimsy defense of Schmitt:

“ Thus one might say that Schmitt is not a counter-revolutionary in a reactionary sort of way. He accepts that legitimacy in this age must be democratic...the point of the analysis of the centrality of the exception for sovereignty is precisely to restore, in a democratic age, the element of transcendence that had been there in the sixteenth and even the seventeenth centuries”

And, further on, in the same introduction, we read:

“[Carl von Savigny] argued that civil law acquired its character from the Volksbewusstsein—the common consciousness of the people—and was thus the product of the particular historically given qualities that a people might have. Hence, for him there was, in the Germany of that time, with its common language and customs, no real basis for different systems of law. For Savigny, the sovereign or legislator was the expresser of the Volksbewusstsein. Schmitt, as we have seen, gives this part of Savigny’s thought very strong emphasis”

Needless to say, the claim that Schmitt is “not a counter-revolutionary in a reactionary sort of way”, merely for the fact that he recognizes the objectively democratic basis of “legitimacy”, is absurd. He is precisely all the more so a reactionary and a counter-revolutionary to the extent that he recognizes this fact and yet formulates a concept of the political that aims to incapacitate the “demo-cratic base” by divesting the demos of its kratos. Kratos is invested by him in a sovereign, a sovereign who acts in the name of a declassed “people”, whereas the demos is objectively a class category (this was even so in ancient Athens). Thus, the class interests of the demos are not invested with sovereign power (that is, with kratos). Whose class interests, then, does the sovereign fulfill when he putatively acts in the “interest” of an abstracted and declassed “people”?

Schmitt substitutes a declassed conception of “Volk” for the much more rooted, historically “sanctified”, and concrete reality of class. Indeed, the idea of a “Volk” apart from class differentiations, as a political idea, is eminently modern, and, in fact, rather abstract—it quite literally abstracts a cultural “genera” to which it then ascribes some sort of normative value. Class, on the other hand, is a lived reality. The aristocrat does not share ties of “Volk” with the plebeian. He belongs to his own “Volk”, one characterized by a shared mode of life, shared political interests, and shared social functions. That “Volk” should be abstracted beyond these concrete class realities and then imposed upon them, imposed irrespective of class distinctions, “across” class distinctions, as it were, is, first of all, an impossibility. This imposition cannot effect an actual usurpation of class by the “Volk”. No matter how much State propaganda one produces valorizing the unified “Volk”, one cannot thereby make class realities disappear. An aristocrat would balk at the suggestion that he belonged to any indeterminate Volkisch mass. The aristocrat is a race apart from the lowly masses, as far as he is concerned. In reality, it is precisely a certain class that wields this “Volk” concept over other classes. In the present, it can only be the bourgeois class that wields this concept over the proletariat and the petty bourgeoisie—to inflame the latter with patriotic fervor, and, where the former refuses to participate in this passion for Blood and Soil, to at least cow them into passive conformity. Though, the latter not infrequently do participate in the very same patriotic mania and bloodlust—there is no magically efficacious principle which precludes the recruitment of sectors of the proletarian class into a bourgeois coalition.

It is rather strange to think that a declassed and abstract “Volk” should become the arbiter of friend and enemy! The “Volk” has no enemy as such, except for that given to it by the same forces which determine that Volk's contours, contours which are never pre-given. The supremacy of the “Volk” concept can only terminate in a “cultural bureaucracy”, that is, the selfsame bureaucratization that Schmitt seems intent on avoiding, only now obfuscated by cultural signifiers that serve to “ennoble” it in superficial assessments. He expresses these fears as follows:

“Today nothing is more modern than the onslaught against the political. American financiers, industrial technicians, Marxist socialists, and anarchic-syndicalist revolutionaries unite in demanding that the biased rule of politics over unbiased economic management be done away with. There must no longer be political problems, only organizational-technical and economic-sociological tasks. The kind of economic-technical thinking that prevails today is no longer capable of perceiving a political idea”

However, it is never a foregone conclusion just what constitutes any given “Volk”. It is, in fact, a highly complex determination, precisely because it is for the most part arbitrary, subject to mere taste. In the aforementioned introduction, for instance, we find the following statement:

“This may make the question of Schmitt's anti-Semitic writings more complex. One might speak of anti-Judaism, meaning by that that Schmitt saw in German Judaism the kind of pluralism that he found incompatible with the commonalty of the Volk that he saw as essential to the political”

Whether or not “German Judaism” is authentically “German” does not seem to be a question that could ever be definitively settled in principle. It is, in fact, a function of how finicky and intolerant one's sense of cultural aesthetic is and of what holds as one's peculiar cultural identifiers. Moreover, the actual project of re-constituting a given “Volk” along lines, determined in advance, that are theoretically determined to be either “authentic” or “inauthentic”, already presupposes a complex social organization and state machinery, that is, a class-based political formation capable of effective action. After all, German Jews already just were a part of the German community as it existed at that time. It necessitated the imposition of explicit theoretical claims (racial theories) and practical determinations (at first, racial laws, and later slave and extermination camps) to modify what, already did just constitute the given “Volk”, in its most passive sense. The Holocaust was not the spontaneous expression of German-ness by some class-indeterminate German “Volk”, but the weaponization of the theoretical construct of “German-ness” by a class-based political formation. The horizon of specific class interests must be assumed if such a project is even to be possible. No “Volk” has ever embarked on a political project as “Volk”. “Volk-ness” is itself a political project, an inescapably modern one, albeit modern in spite of itself.

The basic failure of Schmitt's thinking, then, lies in his failure to adequately distinguish between formal and concrete domains, and this in spite of the fact that his whole conception, putatively, revolves around a rejection of the merely abstract universality of legal norms and in favor of the “concrete” sovereign power that stands above them. The so-designated “concretion” of this sovereign is that of a flesh and blood individual (or group of individuals). This, however, tells us nothing of the intelligibility of this individual's exercise of sovereign power. Sovereign power is never just applied, but always applied in a certain way, toward certain ends, and according to some pre-given logic. This flesh and blood sovereign, as conceived by Schmitt, is therefore an abstraction of the actual historical manifestation of sovereign power. This history is a history of class struggles, and the intelligibility of sovereign power is to be found in the context of these class dynamics, in the application of sovereign power on behalf of this or that class coalition, never just in the application of sovereignty in the abstract. The exercise of sovereign power is socially meaningful, and social meaning cannot be localized to one individual abstracted out of a dynamic whole.

Schmitt, in fact, takes this abstractive defiance of intelligibility to its logical conclusion by analogizing the sovereign decision in the political sphere to the “miracle” in a theological one. Expressed in terms of its most radical consequences, and justifying itself in terms of his primary reactionary influences, this is formulated elsewhere as,

“The true significance of those counterrevolutionary philosophers of the state lies precisely in the consistency with which they decide. They heightened the moment of the decision to such an extent that the notion of legitimacy, their starting point, was finally dissolved. As soon as Donoso Cortes realized that the period of monarchy had come to an end because there no longer were kings and no one would have the courage to be king in any way other than by the will of the people, he brought his decisionism to its logical conclusion. He demanded a political dictatorship. In the cited remarks of de Maistre we can also see a reduction of the state to the moment of the decision, to a pure decision not based on reason and discussion and not justifying itself, that is, to an absolute decision created out of nothingness.”

If “created out of nothingness”, then such decision is, at bottom, arbitrary. Sovereign authority is ultimately reduced, in the Schmittian conception of it, to “pure violence” exercised in an arbitrary manner. Any proper historical survey, however, would invariably show that political dictatorships do not just act arbitrarily. Their acts and decisions are meaningful, premised on rationally explicable interests (even if those interests are not always, initially, conspicuous), the interests of certain class coalitions. The history of real political rule is not the history of inexplicable acts, is not a succession of puzzling mysteries. This history can be studied and fathomed. Hence, we know, concretely, by reference to our knowledge of human history, that authority does not, in actuality, exercise itself in a “miraculous” way. It submits to the intelligible horizon of specific class interests. Formal sovereignty submits to concrete sovereignty. “Pure violence” is a myth, that is, an unscientific concept. “Pure violence and arbitrary will” are not explanations at all, but mere justification, as if to say “I do not need to explain myself. Do not even seek an explanation for my extra-ordinary acts. They are impenetrable mysteries” or “The enemy is not bound by any limits, therefore why should we be?”. The overall purport of the latter, to the effect that we should not harbor too many scruples in engaging with an enemy, may be a perfectly valid justification, but it is no explanation, and we should not accept it as a limit on explanation. Indeed, the explanatory content of the proposition, “the enemy is not bound by any limits” is manifestly false, an excuse to refrain from investigating the intelligible horizon of that enemy's real interests, interests which constitute that enemy's limits, the enemy's intelligible form. “Absolute decision created out of nothingness” is apt as a poetic expression of sovereign authority, but not as a literal or scientific one. Decision is not “absolute”, it comes from somewhere definite, and it derives it meaning from its context within some intelligible horizon. Marxism must insist on science and clarity.

Moreover, this conception of the “miracle” is, itself, ultimately inconsistent with its own theological significance. In terms of the Hobbesian dictum “autoritas, non veritas facit legem”, or “authority, not truth, makes law”, the miracle stands in the place of “autoritas” in juxtaposition to truth—but it is the presentation of “veritas”, that is, of concrete and transcendent truth, which is re-presented by “autoritas”. “The exception, in jurisprudence is analogous to the miracle in theology”, Schmitt says, but in theology it is God who is the source of miracles, and God, theologically, is Truth. Miracle, in its theologically rigorous sense, is theophany, that is, an unveiling of truth in its most eminent sense and in a superlative degree. The miracle is not the abrogation of truth, but of law, the intervention of truth into the formal domain. The miracle, as popularly conceived, appears extra-ordinary and inexplicable because we conflate truth with law, concretion with formality. In reality, the miracle is nothing other than the assertion of the ordinary against that which merely re-presents it (or mis-re-presents it), of the concrete order (from which “ordinary”) against some attempt or another, deemed inadequate by the one who produces the “miracle” on behalf of this concrete order (as its re-presentation), at formally re-ordering it.

The Hobbesian dictum "autoritas, non veritas facit legem", therefore, is fundamentally un-Marxist. Marxism aims to be scientific. It concerns itself with truth. "Authority", therefore, is instantiated in real and concretely intelligible class interests. Class authority asserts itself as a truth, re-presents a concrete truth through a formally organized political movement or institution. It asserts itself as the real existing truth of a historical situation. Authority is not something which can be arbitrarily juxtaposed against truth. Which is to say, the most crucial conception of "authority" is a concretely grounded one, not the merely formal authority that re-presents this concrete ground.

The question of “miracles” is not the limit of Schmitt's theological deliberations, however. There is also the question, given central place in his reflections, of “human nature”. “Every political idea in one way or another takes a position on the 'nature' of man and presupposes that he is either 'by nature good' or 'by nature evil'”, he says, and “this issue can only be clouded by pedagogic or economic explanations, but not evaded”. Note, in the first place, that he equates the question of “human nature” with the question of whether man is “good” or “evil”, at bottom. On this basis he also determines that “Marxist socialism considers the question of the nature of man [read: the determination of man as either “good” or “evil”] incidental and superfluous because it believes that changes in economic and social conditions change man”. In reality, Marx and Engels both make it fairly clear that they are working with a humanist conception of “man”. Just what this “humanism” is, however, is not necessarily clear prima facie. It is, ironically, in the face of anti-humanist protestations against the determination of a positive human essence, precisely the rejection of a positive human essence. The question of the “nature of man” is not reducible to the question of whether man has some determinate essence which is either “good” or “evil”, or, indeed, any other positive essence whatsoever. The eminently Renaissance conception of the “human”, which certainly exercised a decisive influence on Marx and Engels (see, for instance, Engels' high praise of the Renaissance in the “Dialectics of Nature”) is that of “homo faber”, a conception which does not specify the moral value of “humanity”, or any other positive essence. As Pico de Mirandola, putting words in to God's mouth, expresses it:

“We have given to thee, Adam, no fixed seat, no form of thy very own, no gift peculiarly thine, that thou mayest feel as thine own, have as thine own, possess as thine own the seat, the form, the gifts which thou thyself shalt desire. A limited nature in other creatures is confined within the laws written down by Us. In conformity with thy free judgment, in whose hands I have placed thee, thou art confined by no bounds; and thou wilt fix limits of nature for thyself. I have placed thee at the center of the world, that from there thou mayest more conveniently look around and see whatsoever is in the world. Neither heavenly nor earthly, neither mortal nor immortal have We made thee. Thou, like a judge appointed for being honorable, art the molder and maker of thyself; thou mayest sculpt thyself into whatever shape thou dost prefer. Thou canst grow downward into the lower natures which are brutes. Thou canst again grow upward from thy soul's reason into the higher natures which are divine."

Man's nature here is characterized as imitative by virtue of lacking a nature of its own. That is, paradoxically, human nature is no-nature, the absence of any specific nature, and this no-nature manifests itself, concretely, as imitative activity, which is to say, creative and productive activity—as homo faber, whether for good or ill. The reduction of human nature to the question of either its “goodness” or “badness” centers a political conception in which formal authority is elevated to the chief position. In fact, these are just the standpoints of the utopian left and the reactionary right, respectively. In the former, man is essentially “good”, and hence formal authority over man is abhorrent—such formal authority, ironically, becomes an obsession, and the pursuit of its abolition must terminate, as discussed in another essay, with the abolition of industrial production itself. Since this is not really feasible, utopian socialism, in practice, ends up not as the positive project of building an ideal society, but as the negative project of either continually resisting authority or creatively renaming it (as Engels has it “These gentlemen think that when they have changed the names of things they have changed the things themselves”). Reaction, on the other side, primarily centers “man as evil”, and hence elevates merely formal authority, that is mis-re-presentative authority, to a supreme position, as the katechon keeping the rabble in check. “The rabble” is, here, equivalent to “man”, and “man” is “evil”. By extension, the formally invested authorities must be conceived as more than man, as “transcendent” in the mystificatory sense, the sense of an up-there-somewhere beyond man. Hence, the decisions of this formally invested authority appear to be miracles in the sense of that which is extra-ordinary, rather than that which emanates from the concrete order of things. Confirming this relation of reactionary and utopian thought to the determination of man's essence as “evil” or “good”, Schmitt writes,

“Donoso Cortes was convinced that the moment of the last battle had arrived; in the face of radical evil the only solution is dictatorship, and the legitimist principle of succession becomes at such a moment empty dogmatism. Authority and anarchy could thus confront each other in absolute decisiveness and form a clear antithesis: De Maistre said that every government is necessarily absolute, and an anarchist [read: “utopian”] says the same; but with the aid of his axiom of the good man and corrupt government, the latter draws the opposite practical conclusion, namely, that all governments must be opposed for the reason that every government is a dictatorship. Every claim of a decision must be evil for the anarchist, because the right emerges by itself if the immanence of life is not disturbed by such claims. This radical antithesis forces him of course to decide against the decision; and this results in the odd paradox whereby Bakunin, the greatest anarchist of the nineteenth century, had to become in theory the theologian of the antitheological and in practice the dictator of an antidictatorship.”

How ironic that it is actually “the rabble”, or the proletarian coalition, who are as homo faber “beyond good an evil”, and not Nietzsche's would-be aristocrats who, in order to secure and justify their rule, must consign “man” to the status of “evil”, the evil “rabble”. The would-be aristocrat is wedded to the external ascription of evil, its identification with a “rabble” against which he can juxtapose himself. How ironic, also, that it is this same “rabble”, in spite of its constitutional “amorality”, its no-nature beyond any specific moral determination, which seeks to build a peaceful world, a world of abundance and social progress, a good world, and that the would-be aristocrats of the present, always deferring to bourgeois rule, seem destined for war, the impoverishment of the earth, and the multiplication of miseries among their subjects. “Good” may not be the nature of the proletarian “rabble”, but it is their foremost creative production—and they are as capable of producing good for their friends as they are at manufacturing evil for their enemies.

This opposition between a pseudo-aristocracy and a “rabble”, that is, of declassed political conceptions, is not exclusive either to Nietzsche or to Schmitt. It is fundamental to reactionary political thought as such. As Schmitt tells us, “Catholic political philosophers such as de Maistre, Bonald, and Donoso Cortes”, among his most prominent theoretical influences, “are called romantics in Germany because they were conservative or reactionary and idealized the conditions of the Middle Ages”. We are not, however, in the Middle Ages any longer. There are no longer any kings, even according to Cortes, as shown in an earlier quotation. Reactionary political thought, therefore, reduced to its essence, is a nostalgia for aristocratic rule over “the rabble” adapted to the concrete absence of a meaningfully “aristocratic” class. There is no longer an aristocracy, but "the rabble" still need to be ruled over. This is the problem that reactionary thought is continually grappling with: the purely negative imperative to suppress the rabble. It asks "how can this be done under present day social, political, and economic constraints?". At the same time, it provides ideological justification of why it must be done, of why "the rabble" is a danger to society, why "virtue" can only thrive in their pseudo-aristocratic political formations. Implicitly, therefore, reaction acknowledges the very same class analysis that forms the basis of Marxism. It must do this because that analysis unveils a concrete truth. Reactionary theoretical disquisitions are, thus, at the same time a protracted effort at theoretically obscuring this basis in the actually existing class struggle, and providing practical guidelines for the concrete political suppression of that which it designates “the rabble”, and which turns out to be, concretely, the proletarian coalition. These same “aristocrats”, in turn, must be, objectively, members of the bourgeois coalition—insofar as they stand against the modern “rabble”, and insofar as there is no genuine aristocratic coalition, a “modern aristocrat” can belong to no other faction than that of the bourgeoisie. Ironically, if any class, today, could constitute a genuine aristocracy it is only an armed proletarian class coalition. This is the only class that could found itself simultaneously on its force of arms and on its concrete groundedness in the polity. Bourgeois power, unlike the nomadically grounded aristocracy, is founded not on any kind of concrete presence as such, but on the mis-re-presentation of that presence, the presence of the proletariat at the site of production.

Curiously, as indicated in an earlier quotation, Schmitt acknowledges that the basis of any modern political formation, including any putatively “aristocratic” one, must be democratic; in his words, “the idea that all power resides in the pouvoir constituant of the people, which means that the democratic notion of legitimacy has replaced the monarchical”. This basis, according to Schmitt, unless handled properly, poses a threat to the transcendent dimension of politics. He explains,

“The general will of Rousseau became identical with the will of the sovereign; but simultaneously the concept of the general also contained a quantitative determination with regard to its subject, which means that the people became the sovereign. The decisionistic and personalistic element in the concept of sovereignty was thus lost.”

Framed theologically,

“It is true, nevertheless, that for some time the aftereffects of the idea of God remained recognizable. In America this manifested itself in the reasonable and pragmatic belief that the voice of the people is the voice of God - a belief that is at the foundation of Jefferson's victory of 1801. Tocqueville in his account of American democracy observed that in democratic thought the people hover above the entire political life of the state, just as God does above the world, as the cause and the end of all things, as the point from which everything emanates and to which everything returns.”

And,