Left, Right, Third Position, and the Specter of Communism

Communism is a Future which is already Present

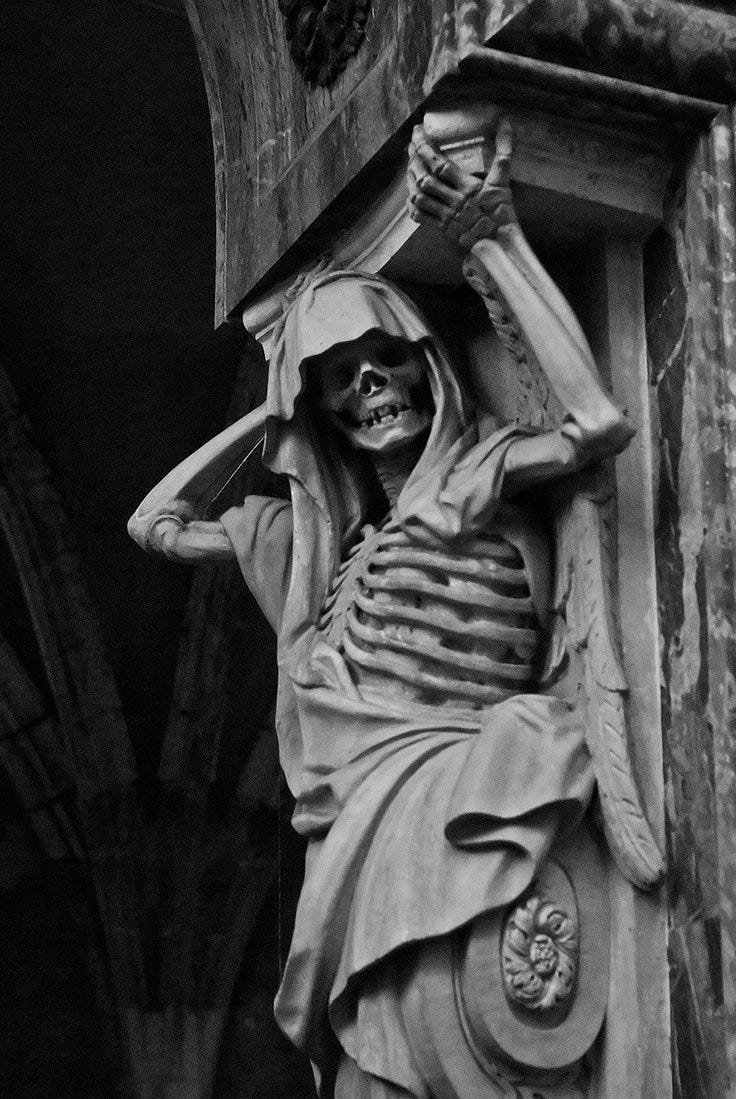

“A specter is haunting Europe—the specter of communism”—If communism is a specter, then, as specter, it must first be encountered in the form of a haunting. This is, after all, what specters do. What is communism haunting? How is it haunting it? In what manner does this invisible “something” become something visible for us?

The original criterion for left-versus-right wing is the triad of liberty-equality-fraternity. Originally, liberalism was a left wing ideology. That is, the radical liberal revolutionaries who stood on the left side of the French National Assembly were most radically dedicated to these ideals, whereas those on the right wished to make compromises with the aristocracy and the like. This is the historical origin of the distinction, in the French Revolution. Liberalism, however, was displaced as a left wing ideology (or, in any case, as leftmost) when it was show by Marx to fall short of its own criteria. It was dedicated to a mere ideal. Communism upholds the ideals of liberty, equality, and fraternity, but it also aspires to make them real, to establish them concretely in social conditions. Marx revealed that there was a position further to the left of liberalism, according to its own criteria.

Not only did Marxism reveal a position further to the left than was hitherto considered, but this “revelation” itself necessitates a total reorientation of the political spectrum. In light of this, we must judge political factions on more concrete criteria. The “ideas” this or that group upholds, taken on their own, are of little consequence. What are they actually striving to bring about? What are the practical correlates of their “ideas”? This reorientation of the political spectrum not only changes the criteria by which we assess it, but reshapes the topology of the spectrum—from a line into a horseshoe. It is only Marxism which reveals that the political spectrum was a horseshoe to begin with. Communism was always, in ghost-like fashion, haunting the space between the old feudal order and the new revolutionary liberal one. Marx only made this haunting more explicit.

If liberalism sees in liberty-equality-fraternity revolutionary ideals, then feudalism also must stand in some relation to these criteria—they are criteria dividing the self-same political spectrum. Liberalism did not invent these ideals, but inherited them ready-made from the preexisting feudal order. In the one case, they are revolutionary ideals, and, in the other, they are the “natural” and really-existing expressions of a providential hierarchy. The feudal world is not interested in the pursuit of ideals, but in the world of nature as an expression of God’s providential designs, and that design bears the same triadic structure of liberty-equality-fraternity, only expressed rather differently.

Liberty, in the world peculiar to feudalism, is, on the one side, the security afforded for the peasantry and the cities by the aristocratic military caste, and, on the other, it is the otium of that military caste during those periods when they are not preoccupied with the arts of war. Liberty is, for those lower on the hierarchy, liberty from harm, and, for those further up the hierarchy, liberty for refined leisure activity.

“Equality”, for the feudal order, is the equality of equals, and the inequality of unequals. It is the Platonic conception of Justice, that everyone knows the place allotted to them. It expresses itself in noble courtesy. Every man of noble birth is “on the same plane”, as it were. Even the king merely performs a superior function in the hierarchy. In terms of his “essence”, however, the king is no different from any other man of noble birth. If he should attempt to usurp more for himself than is his natural due, then the other noble lords are within their rights to depose him and install a new king. “Fraternity” is the implied bond of obligation attached to these hierarchical ties—loyalty, service, obedience. “Fraternity” means that the relations of older and younger sibling, the relations of father and son, the relations of husband and wife, involve mutual, albeit unequal—“only equals are equal” is the feudal formula—obligations.

For the feudal order, liberty-equality-fraternity is a concrete state of affairs embodied in the actual organization of society. For the liberal, liberty-equality-fraternity represent ideal “rights”, but these rights are disembodied from the material organization—and, not only this, but that material organization actually precludes their possible realization. Under capitalism, then, these ideals are doomed to remain mere ideals. This is why the liberal revolutionaries fundamentally tend toward utopianism. The further left the liberal revolutionary is pushed, the more utopian he becomes. Capitalism is a practical compromise.

Liberty is his ideal—the liberty to live as he pleases, the liberty from outside compulsion. There is a fork in his road. He has split liberty in two. He can choose the compromised liberty of capitalism, the liberty of the property owner to do with his property as he pleases, or he can choose the idyllic liberty of the socialist utopia, the liberty from the compulsion of property relations. The former liberty implies the subjection of the non-owner, in fact. That is, the ideal of liberty only exists as the factual liberty of the property owner. The liberty afforded by capitalism is his liberty alone. The liberty of the owner is the full stomach afforded by his property, and the liberty of the worker is the empty stomach afforded by a mere ideal.

How, then, do the utopian radicals—the “left liberals”, if you will—propose to resolve this property debacle? What utopianism strives to bring about, frequently in an unconscious manner (though some utopians have been thorough enough to bring this out explicitly), is a de-industrialized society. Utopianism, when pursued beyond its mere idealizations, and into its practical implications, must culminate in some form of Luddism. The large-scale social organization necessitated by the industrial mode of production is always bound to conflict with the idyllic aspirations of the utopian. The management of large-scale industry requires centralized coordination. A complex and vast industrial base cannot be managed through the spontaneous brotherhood of man. Since such a large scale industrial base cannot, in fact, be organized by spontaneous feelings of brotherhood, the idyllic socialist utopia, in order to realize itself in any measure, must return to a predominately agrarian mode of production—that is, it must return to feudalism. The idyllic life of utopian socialism, to the extent that it is capable of becoming a fact and not a mere ideal, belongs to the small scale, self-sufficient community. Even then it is only a matter of degree. This ideal is negative, and perpetually flees from any attempt to actualize it.

Herein lies the horseshoe structure of the political spectrum: the liberal revolutionary cannot realize his ideal unless his ideal becomes his invisible monarch, and every man becomes both feudal lord and peasant rolled into one—peasants in their subservience to the ideal, and feudal lords in their ties of brotherly equality. Every man owes his brother both the courtesy shown by one lord to another, and the noblesse oblige shown to an inferior—an orgy of universal brotherhood expressed as pity. In its proximity on the horseshoe to the far-right position of feudalism, liberalism comes to resemble the feudal order in many ways. Both, in order to be actually and “authentically” realizable, require de-industrialization. Both imply a belief, whether explicit as in feudalism, or implicit, as in utopianism, in a providential order with a binding, normative value. Utopianism is a monarchy without a monarch. It is an inverted fuedalism. The kingdom of heaven is realized outwardly in a harmonious social order, and the feudal order is transposed to the inward life as obedience to the “monarchy” of the ideal. Both of these position bear curious resemblances to fascism.

Fascism is indeed a “third position”, but it is not the third position between capitalism and communism. It is the third position between feudalism and utopian socialism. Which is to say, capitalism itself is the third position ideology, and fascism is simply the ultimate expression of capitalism. Fascism is not just a type of “centrism”, it is fixed at the absolute dead-center. Fascism is most reactionary not in its extremity—feudalism is more “extreme” than fascism, that is, belongs to the extreme end of the spectrum—but in its intensity. It is the most intense bulwark against the “danger” of communism.

Capitalism itself is a sort of “centrism”, and always represents itself as such. Fascists, from the beginning, represented themselves, albeit falsely, as a center position between the extremes of communism and capitalism. Neoliberalism, in the contemporary United States, though no one actually calls themselves by that title, can be generally represented as the middle position between the so-called “populist right” and the social-democratic (hardly) or “welfare-state” left. Social Democracy itself constitutes a sort of contemporary European centrism. So capitalism, regardless of the guise under which it travels, does tend to represent itself as a centrism, though it generally does this by obscuring the actual criteria by which it could reasonably be defined as centrist. Fascism is not the most extreme form of capitalism (since capitalism is a middle position, and does not belong to the extremities), but its most intensified form.

Since fascism constitutes the middle position on the spectrum, it must also bear some relation to the triad of liberty-equality-fraternity. Fascism takes the liberty-equality-fraternity of the feudal order, and makes it into a revolutionary (or, rather, pseudo-revolutionary) ideal. It takes the revolutionary pathos of the utopians and transposes it onto a pseudo-feudal social organization. The prefix “pseudo” must continually recur for us in any assessment of fascism. It is the ultimate counterfeit ideology, the maximal expression of capitalism’s ability to produce illusions. Under fascism, the function of illusion is no longer to serve as the mere circus of mediating distractions that constitute the liberal bourgeois state, but illusion itself become apotheosized as the ideal representation of the residually feudal characteristics of capitalism. That is, capitalism already has some residual feudal elements to it (it is, after all, a middle position between feudalism and utopian socialism)—elements such the hierarchical structure of private industry—and fascism idealizes those elements as though they were part of the natural “providential” order. The links between fascism and “Social Darwinism” are not accidental. “Social Darwinism” is the scholasticism of the capitalist, his theology of “natural law”.

In this sense, capitalism is the conflict between two interpretations of one triad of ideals, and both interpretations are present in its manner of organization. The bourgeoisie are the aristocracy of capitalism, an aristocracy that frequently prides itself on its “work ethic”. The workers, they say, are poor because they are lazy and stupid. We, they say, are successful because we are the best workers. The natural order of feudalism and the revolutionary ideals of liberalism are in perpetual flux and conflict within the world of capitalism.

Fascism takes the perpetually moving conflict of the utopian and the feudal, which is always present in capitalism, and attempts to freeze it. Fascism is the ossification of this conflict, the attempt to stabilize a “moment” of this flux into a fixed and permanent social order—into a “natural” social order. It is a pseudo-aristocratic (and aristocratic always also means militaristic) safeguarding of capitalism.

Marxism is not at the center of the horseshoe, but beyond its extremes. Marxism makes the ideal a reality, and the reality conformable to the ideal. This is not to say that Marxism makes reality “idyllic”. It is to say that the ideal and the real are paradoxically entangled as mutually defining criteria. The real, as the current situation under capitalism, is assessed according to its inability to realize the ideals which gave it birth. And the ideals of liberty, equality, and fraternity are assessed according the manner which they can actually come into fruition within the context of certain prevailing material conditions. Marxism asks: “how can these ideals actually be realized under these prevailing material conditions?”. Fascism asks: “how can these already prevailing social relations (capitalism) be mythologized, and strictly enforced, as an ideal?”.

The reason communism is “left wing”, despite its position beyond the extremities of the horseshoe, is because the historical point of access to it is through the liberal revolution (hypothetically, a theoretical point of access from the right should be possible, though it would be highly exceptional). It is not the left wing of liberalism. “Radlibs” are the left wing of liberalism, the utopian wing of liberalism. Communists are the left beyond liberalism. Communism is, as a historical trajectory, approached from the left, so to speak, and not from the right. Communism comes after capitalism. It comes after liberalism. It radicalizes the liberal ideals by concretizing them. This is not to say that communism, in order to be brought about, must pass through all the “degrees” of capitalism and thence into utopian socialism. The history of revolutionary socialism, at the least, disproves this. Neither the USSR, nor the People’s Republic of China, nor Socialist Republic of Vietnam, nor the Republic of Cuba, etc, were “developed” nations. Communism does not need to be brought about through incremental “reformist” steps—because it is already here. It is here as a specter. Communism is always tacitly present, even if not yet actualized, as long as the industrial mode of production is present, and this mode of production is a global reality. Communism is here because the ideals of liberalism have come to birth, and the real feudal order is still present in the structure of private industry. Communism is the implied union of real and ideal, a union that transforms the character of both—an “alchemical wedding”. Its very existence is already implied in the background of our political spectrum. It simply requires revolutionary will and action to realize it.

There is a katechon standing sentinel over the political spectrum, the katechon of industry. It prevents any real movement toward the left (the utopian left) and toward the right (the “feudal”-reactionary right). Without de-industrialization, achieving the aims of either of these camps, in a real way, is not possible. Real, concretizable, movement toward either extremity is a practical impossibility. The exclusion of the element of praxis makes the element of fantasy present in these ideologies all the more potent—feudal-romantic fantasy, fantasies of utopian social harmony. To whom does that fantasy belong? An unreal dream always belongs to a real dreamer. The fantasies of the political extremities belong to the only thing today which is real—to the center, to capitalism. That is why the center always subsumes these tendencies to itself. Capitalism is the dreamer, and the political extremities are the dream. The right-subsumption is Fascism, and the left-subsumption is liberalism (liberalism is the phony utopianism, the utopianism of words—it suffices merely to say that one is “free”, that one has “rights”)—both are instances of bourgeois rule, of bourgeois appropriation of ideology, and therefore both subsumptions occur at the center, though one decks itself in a “rightist form” and the other in a “leftist form”. Only the specter of communism can save us. It is present from out of our future, even when seemingly absent. It is always already here. We need not go wandering to the left or to the right in order to find it. All those who wander are lost. All movement to the left and to the right takes us back to the center, every right-deviation toward a right-subsumption and every left-deviation toward a left-subsumption.

The specter of communism calls on us to reject the merely real, the all-too-real. Revolutionary epistemology lies beyond the real-ideal distinction, beyond the distinction between action and contemplation, just as communism lies beyond the political spectrum. It is not part of the spectrum, and yet it is always present within it—it is, in other words, a specter. It is, to use another expression, the more-real concealed within the not-real-enough. What is the not-real-enough? The illusion of capitalism, the illusion of bourgeois rule by virtue of fiat declaration of ownership. What is the more-real? The actual, existing power of the working class by virtue of their possession of the means of production. The worker already has power, already has sovereignty—he simply has to awaken from this dream and actualize it. Communism is already here, a specter from out of our future, more real than mere “real life”. “Real life” is concocted in corporate marketing departments. Communism is forged in the real furnace of working class-community. Communism is the ghost of a future life which is more real than the present, even in its ghostly presence here and now.